Thursday, April 20, 2006

I know that Father Bob has had a whole series of articles published in his local newspaper, because he has copied them here.

My local paper has also published an article about my trip to Lui. It's currently at the News-Tribune website.

I'm very happy to have that publicity, if it will make folks in my region more aware of the issues confronting folks in Africa.

On the other hand, I do need to offer some "notes of exception" to that news article.

First, as most of you know, I was not there for a month; it was only twelve days. Since I provided the reporter with a copy of our itinerary, I’m not sure how she made that error. But there you have it.

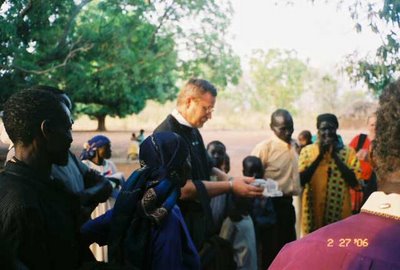

Second, I regret that the reporter did not key in on a theme that was very much a focus of my comments: namely, the role that my local parish, other friends, and family provided in supporting me before (with encouragement and funds), during (with prayer), and after (with interest and patience) the trip. What she also failed to note is that the book (Gospels in Glass) I’m handing to Morris in one of the photos was written by two of our parishioners, and it includes two of Grace’s own stained-glass windows. I really liked leaving that memento in Lui – a particularly special gift from Grace to Lui.

Finally, there’s the contrast between my story and that of the other woman in the article. Folks here tell me they perceive a clear distinction between why she and I went on our mission trips and between what she and I took away from those trips. Our diocesan group did not go to southern Sudan to “convert the heathens.” Our two Episcopal dioceses (Missouri and Lui) are in the process of finalizing a “covenant agreement” to specify how we will assist and support one another. I have no doubt that I took away from that trip much more than I contributed.

All that said, the article is not bad. And, with any luck, it might make some folks think more deeply about the situation confronting our friends in Africa.

While we were in the Lui compound, it was clear that sanitation was important. This little stand became very important to us.

While we were in the Lui compound, it was clear that sanitation was important. This little stand became very important to us.The people of Lui observed careful hand-shaking rituals, depending on whether one's hands were clean or not.

The Moru kept this pot topped off with water so that we could wash our hands frequently. You’ll also notice the bar of soap at the right.

Breakfast

When we first arrived in Lui, the Moru worked hard to make nice breakfasts for us. But I think they figured out that we were not big breakfast eaters. Mostly, we just wanted our coffee!

So they seemed to slack off – which was more than OK with us!

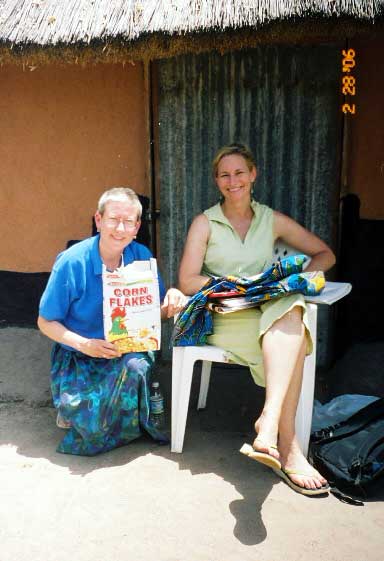

Eventually, we realized they were leaving mostly cereals for our breakfast. Uncle Russell, this one’s for you! Corn Flakes made their way to Lui. I don’t expect anybody outside of my family to understand this photo.

I’m not sure why we got more reflective and photographic on Wednesday. No, that’s not true. I think I do know why we did that. I think it’s because we knew we were going to be leaving Lui the next day. And so we wanted to capture the experience, the perceptions, the odd little moments. We captured strange little odds and ends.

Because the lack of a vehicle made Wednesday odd, we had more time to pay attention to our village life.

Sandy and Deborah got some relaxing time.

Sandy and Deborah got some relaxing time. This is the “VIP Tukal,” where Archdeacon Robert stayed. I understand it's also the tukal where our Bishop stays when he goes to Lui. Probably that's because it’s the largest tukal. But, ironically, it’s also the tukal that’s closest to the latrines. So .. nobless oblige, I suppose.

This is the “VIP Tukal,” where Archdeacon Robert stayed. I understand it's also the tukal where our Bishop stays when he goes to Lui. Probably that's because it’s the largest tukal. But, ironically, it’s also the tukal that’s closest to the latrines. So .. nobless oblige, I suppose.I caught a shot of Deborah with Anna, the woman who had done the bulk of our cooking. Even when we tried to thank her, she was just too modest to stay with us for very long.

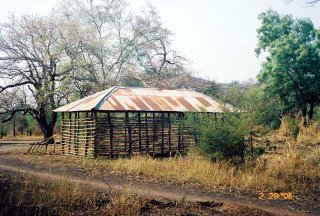

Lui has a carpenter. There are no WalMarts or Lowes or Ikeas in Lui. If you need something built, you must have it built it Lui. If I understand correctly, this is the shop of the one and only carpenter in Lui.

Our builder and carpenter, Rick, got the chance to visit with him. I hope Rick will “chime in” here with his observations.

Our Rick in front of the carpenter’s shop.

I'm sure Rick will not tell this himself, so I'll put it here in the blog until Rick sees it and makes me remove it. I think Rick is probably a very big contractor in his urban area. And I think one reason he was invited on this trip is that the people of Lui wanted advice about building and construction. Rick would have been well justified in introducing himself as a big contractor. But that's not what he did. All over Lui, wherever he went and whomever he met, he simply introduced himself as "a carpenter." I was touched and inspired by his humility.

Rick, my brother, you were an inspiration to me!

Waiting for Water

Waiting for WaterIf I understand it correctly, there were two boreholes within "reasonable" walking distance of Lui. This was the one we passed on our Ash Wednesday walk.

People were gathered all around it. And I noticed lots of water containers placed all about. Later I learned that it’s because of the drought. Women would come to the well, hoping to find water, but there was none. So they would just leave their container and go on about other business, coming back later in hopes of water.

What’s the deal with the water? It took me a long time to understand it, and I’m not really sure I do even now, but at least I understand more than I did before.

Yes, there are a few wells in Lui. Not many, mind you. They are spread about 5 miles apart. Try to imagine that, my U.S. friends. Try to imagine having to walk 5 miles to get enough water for your family to get through a day … or two … or three.

Yes, there are a few wells in Lui. Not many, mind you. They are spread about 5 miles apart. Try to imagine that, my U.S. friends. Try to imagine having to walk 5 miles to get enough water for your family to get through a day … or two … or three.Then add this: The drought in Lui is so severe that even the wells are running dry. You walk half the morning to get to a well. But the well isn’t producing any water. You have to wait until the water can slowly trickle through the granite substrate and come trickling into the bottom of the well again.

Meanwhile, many other peoples’ water containers sit gathered around the well … waiting and hoping …

Finally, the water starts flowing again.

Maybe you’ll be one of the lucky ones who gets her water container filled. Maybe your water will be clean. Maybe – just maybe! – you’ll get water that is not contaminated with cholera or any of the other many water-borne diseases in Lui.

Maybe you’ll be one of the lucky ones who gets her water container filled. Maybe your water will be clean. Maybe – just maybe! – you’ll get water that is not contaminated with cholera or any of the other many water-borne diseases in Lui.I cannot tell you how many women I met who were spending their entire day trying to collect water for their family. It was breathtaking to me. The lucky few women who have (supposedly) “paying” jobs at Samaritan’s Purse hospital, who would spent their entire day off walking back and forth to one of the wells, hoping to collect enough water to take care of their family during the next week.

And I saw this a lot, too: We would be coming home in our truck at night – maybe 8:00 p.m. or later. And I would see women walking along the track toward the well. Why? Because it’s cooler in the night, when you have nothing but the meager moon to light your path. But at least you do not have to walk in the 110-degree heat that greets every day in Lui!

I was overwhelmed by the struggle it takes merely to survive in Lui. Remember Maslow’s pyramid of the basics of human existence? Water. Food. Shelter. Merely getting water could kill me in Lui. It’s that difficult.

And here’s another complication. When our Bishop first explained the water situation to my parish, before I made the trip to Lui, he stressed the need for water and wells and boreholes. We all wanted to do something to dig deeper wells. But then he had to explain to us the Lui hesitance to dig deeper wells: They are afraid to dig deeper wells, because the oil is so near the earth that they might accidentally strike oil. And our western minds said, “Yee-haw! ‘Black gold!’ ‘Texas tea!’” But no. One of the significant reasons that the northern Khartoum government waged war against the South for 2 decades was because southern Sudan has so many natural resources, and the Khartoum government apparently covets those resources. So if you try to drill a deep well in Lui to provide water for a village – but accidentally hit an oil well – there’s a risk that the Khartoum government will learn about it, and come in and destroy your village and your family and neighbors. So – weird as it seems to me – digging a deeper well is actually a risk and one that you probably do not want to endure.

So the people die of thirst, because digging deep wells might bring renewed warfare due to the lust for oil. How sick is that??!!??

And what will it take to quench this people’s thirst?

I’ve talked before about how the people of Lui are hesitant to build or re-build with mud structures, opting to build of grass instead. Building in grass is faster, and less expensive.

These are some grass bundles, harvested and waiting for buyers.

It was pretty fun to see this sight -- a guy riding along the road on his bicycle with grass bundles as cargo. But that also led me to wonder what's going on here. I would have thought that -- with these tall grasses so plentiful throughout Lui -- everyone would just go into the brush and cut his/her own grasses to make roofs or shelters. Not so! I do not understand the reason, but I gathered this information: Most people do not go out and cut their own grass. Instead, they have to buy it. And it is expensive, by Sudanese standards: something like $1US per bundle. And it takes something like 100 bundles to make a roof. So, in fact, the grass cutters are upper-end businessmen.

It was pretty fun to see this sight -- a guy riding along the road on his bicycle with grass bundles as cargo. But that also led me to wonder what's going on here. I would have thought that -- with these tall grasses so plentiful throughout Lui -- everyone would just go into the brush and cut his/her own grasses to make roofs or shelters. Not so! I do not understand the reason, but I gathered this information: Most people do not go out and cut their own grass. Instead, they have to buy it. And it is expensive, by Sudanese standards: something like $1US per bundle. And it takes something like 100 bundles to make a roof. So, in fact, the grass cutters are upper-end businessmen.My U.S. brain just overloads at that point. I do not understand how such a basic building material -- which is in such great supply in Lui -- can be so difficult for most people to afford. Maybe one of the next travelers to Lui can help me (and us) understand that dynamic.

As we walked the road, we noticed that this is how clothes are dried. I never did see the process for washing clothes. But this is how they are dried all around Lui: draped over bamboo fences.

As we walked the road, we noticed that this is how clothes are dried. I never did see the process for washing clothes. But this is how they are dried all around Lui: draped over bamboo fences.

All around Lui, we would see sights like this. The terrain was very scrubby brush. But then, rising out of nowhere, there would be this awesome mango tree. They created the most wonderful, cool shade. People often gathered under the mango trees.

All around Lui, we would see sights like this. The terrain was very scrubby brush. But then, rising out of nowhere, there would be this awesome mango tree. They created the most wonderful, cool shade. People often gathered under the mango trees. Hmmmmmmm…. I need to think of a good reason to include this photograph – preferably some profound theological insight. Let’s see .. some insight into the Garden of Eden and how Adam and Eve covered their nakedness with big leaves? … Well, I can’t come up with one. This just made me laugh. In this scrubby landscape, there were some trees that made huge leaves. And this one was just big enough to serve as a fig-leaf for me.

Hmmmmmmm…. I need to think of a good reason to include this photograph – preferably some profound theological insight. Let’s see .. some insight into the Garden of Eden and how Adam and Eve covered their nakedness with big leaves? … Well, I can’t come up with one. This just made me laugh. In this scrubby landscape, there were some trees that made huge leaves. And this one was just big enough to serve as a fig-leaf for me.

It took me quite a while in Lui to get my head around the role of the Mother's Union. At one point, checking my understanding with one of my fellow travellers, I asked, "So they're kinda like the Altar Guild ... but on steroids?" No. More. Much more. They don't merely take care of the cathedral and parishes. They take care of the community. They establish schools. And, apparently, they try to find better, more efficient ways for women to provide water and food for their families. I still don't quite "get it." But I do "get" that they are a force to be reckoned with ... and a major force for good.

The Mother’s Union is working very hard to establish schools – not just for children, but also for adults (and especially women). This is one of the adult literacy centers they have built.

It is designed partilarly for the women of Lui. Here, Father Bob is at left, and Mama Margaret is at the right. I can't remember the name of the priest in the center.

And this is one of the children’s schools. If I understood them correctly, this is for middle-school students. And our kids think they have it rough!

This is another of the “classrooms.” Class is not in session now, but our friend Rebekah took a breather here.

Note the style of these seats. I saw these all around Lui -- especially in schools and in church buildings. They drive a forked branch into the earth, then stretch a limb across those supports, and – voila! – a bench or seat.

This is a sight we saw all over Lui. It took me several days, though, to understand what I was seeing.

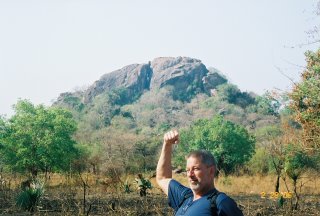

Throughout Lui, the granite outcroppings are everywhere. If you have seen Georgia’s Stone Mountain, you’ll know what I mean. There are granite outcroppings all over the place. And that’s one of the challenges of traveling by “truck”: You are forever climbing and descending on those rocky outcroppings.

And as we traveled these Lui roads, I would see those strange piles of rock. Piles of huge rocks, big rocks, smaller rocks, and tiny rocks. It took a while – and some talking with our Lui hosts – before I understood what I was seeing.

They use these rocks as building materials – to “chink in” their mud or plaster structures.

But how do they create that gravel? They take shards from the granite mountains and outcrops, chisel them down to "merely" huge rocks, and pound them down to big rocks, then pound them into small rocks, then finally pound them down to gravel. Mind you, they’re doing all of this by hand! They do it by the side of the road. Why? Maybe because it’s easier to transport them? I don’t know. I just know that I saw these piles all over Lui. Most of the time, I saw men at work, pounding the rocks into smaller and smaller rocks.

They do it by the side of the road. Why? Maybe because it’s easier to transport them? I don’t know. I just know that I saw these piles all over Lui. Most of the time, I saw men at work, pounding the rocks into smaller and smaller rocks.

With the truck dead, and the realization we weren’t going anywhere for a while, we got a little “stir-crazy,” and happily took the Lui women’s invitation to walk around the areas surrounding Lui. We went roughly east toward a village they called ”Lwan-JEE-nee”. Sandy & Deborah were off working at Samaritan’s Purse. The rest of us (Archdeacon Robert, Father Bob, Rick, and I) went, accompanied by Mama Margaret, Mama Janifa, Rebekah, and Lois.

One of the first sights that caught my attention was these guys.

We did not know them. Never met them. But they were heading off to their farm work, with their tools. They had no tools more sophisticated than a hoe and pickaxe. There is a local blacksmith who – when he can get metals to work with – can fashion primitive implements. And this is what they have to work with. This is all they have to work with. There are no fancy farm implements, and there are no farm animals. Just hoes and axes.

We did not know them. Never met them. But they were heading off to their farm work, with their tools. They had no tools more sophisticated than a hoe and pickaxe. There is a local blacksmith who – when he can get metals to work with – can fashion primitive implements. And this is what they have to work with. This is all they have to work with. There are no fancy farm implements, and there are no farm animals. Just hoes and axes.As we walked through the desert scrubland, there were some marvelous sights. The mountain in the background is called Mount Ordu.

As we walked down the road, we saw all sorts of signs of life. One was this sight off to the north, of people putting the roof on a tukal.

I don’t fully understand how much time and skill and money is required to put the grass roof on a tukal, but I have begun to understand it’s much more complex than I imagined. These fellows saw us admiring their work, and they stopped to wave back to us.

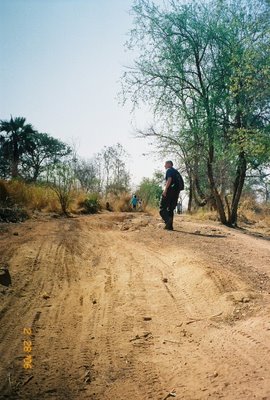

I don’t fully understand how much time and skill and money is required to put the grass roof on a tukal, but I have begun to understand it’s much more complex than I imagined. These fellows saw us admiring their work, and they stopped to wave back to us.  I’ve written many times here about how rough and primitive the roads were. I tried taking photos several times, in hopes that one of the photos would communicate the roughness of those “roads.” None of them really did it, but I’ll post these here, in hopes they might serve as an indicator. These were among the better, smoother roads. That’s Rick in the frame.

I’ve written many times here about how rough and primitive the roads were. I tried taking photos several times, in hopes that one of the photos would communicate the roughness of those “roads.” None of them really did it, but I’ll post these here, in hopes they might serve as an indicator. These were among the better, smoother roads. That’s Rick in the frame.

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Beehives

BeehivesI was intrigued by the way the Moru people collect honey to satisfy their prodigious sweet tooth. And by the way, their honey is marvelous! It was one of my favorite treats on the trip.

I did not have a chance to observe their bee-keeping practices. Others in our group encountered the bee-keepers on one of the days when I stayed in Lui. But I’m fortunate to have their stories and photographs, and I hope maybe one of our other missioners might provide some more details in the "Comments" section.

On one of the first days out of Lui, our team encountered some beekeepers. Here they are with one of their beehives. They weave them themselves, out of the grasses that grow nearby.

As we rode along the roads of Lui, we would see these things up in the trees. They baffled me at first. But then one of our team members explained to me this was one of their beehives, up in the branches of a tree.

Here – during one of our village visits – is one of their grain storage bins. Under the bin, you can see one of the beehives stored.

And you can see how they have stashed a beehive up beside a grain storage bin. Deborah is in the foreground.

Sunday, April 16, 2006

I did not know about this, but apparently Deborah told some folks in the Diocese of Missouri that the Moru needed and wanted reading glasses – the drugstore-type of reading glasses that many of us 50-somethings are using nowadays. And Rick had carried dozens upon dozens of eyeglasses in his luggage. When we visited Buigi, I got to see the fruits of that gift.

After we worshipped with them, Deborah brought out the “eyeglass offering,” and it was truly delightful to see the folks try them on, with each person seeking to find the right “’prescription” for them.

After we worshipped with them, Deborah brought out the “eyeglass offering,” and it was truly delightful to see the folks try them on, with each person seeking to find the right “’prescription” for them.There’s one aspect of this that you can’t tell from the photograph.

Just about the only book they seem to have is the Bible. So, as those folks tried on their reading glasses and worked to see which strength they needed, others in the village held up Bibles so they could test their new eyeglasses. It was a moving time.

Just about the only book they seem to have is the Bible. So, as those folks tried on their reading glasses and worked to see which strength they needed, others in the village held up Bibles so they could test their new eyeglasses. It was a moving time.Deborah was amazed at how the folks of Missouri had responded to the needs she had expressed. More than once, she said, “I swear, if I had said the Moru needed ice cubes, you all would have found a way to get them here!”

We had been told to expect the truck to arrive early Wednesday, but it did not come and did not come. Having grown accustomed to East Africa Time, we were not unduly concerned. (It was much later when we learned that our truck had gone belly-up, and that the Lui folks were scurrying to find us an alternate vehicle.)

But some of our fellow travelers arrived in the guest compound, and they began talking with and challenging our missioners. Mama Margaret, Rebekah, and (I think) Mama Janifa and Lois had appeared in the compound, and they began quizzing Archdeacon Robert, wanting to know the details of the companion relationship agreement between the Diocese of Missouri and the Diocese of Lui. I was in my tukel at the time, and just overhearing this conversation. But a couple of things struck me.

First, some of these women had been present when we had talked about these items in the archdeaconry meetings. Why had they not spoken-out then? Was it because they defer to the men who were present?

Second, the issues these women raised – and raised very passionately – were somewhat different than the issues the men had raised in our archdeaconry meetings. The women spoke of education – the need to provide education not just for the children of Lui, but also for the young adults who have been deprived of education as a result of the past two decades of civil war during which there have been no schools. They also spoke strongly of the need for infrastructure that can empower women – especially the need for grinding mills, which could free-up women’s time so they could go to school.

Hearing this exchange, I began to develop this hypothesis: Even if we think we are giving the people of Lui an opportunity to speak, we need to make space for sub-groups – such as the women of Lui – to speak alone. Because I have a hunch that they are not going to speak when the men are present. Or at least that's my hypothesis, having seen this strong, smart women sit quietly in the archdeaconry meetings, then speak so clearly and forcefully with a small subset of our diocesan group.

When we began stirring around the compound this morning, we learned a sad fact.

Last night, after our driver (Manyagugu/a.k.a. Father Darius) dropped us off at the Lui guest compound, he then drove on to take another of the clergy home. On that drive, the truck bit the dust. Apparently, the truck is now dead by the side of the road, probably with a broken drive shaft. It will stay there until someone can buy, find, or fabricate new parts.

That’s so illustrative of the basic lack of self-sufficiency. In Lui, you can’t just run down to the nearest parts store. There are no mechanics! There are no parts stores! If a new part is required, they are going to have to wait until somebody can send a new part from Kenya or elsewhere.

One thing I heard in Lui was various young men expressing the desire to become mechanics – and of their desire to go to school to learn mechanics. I wonder: How can we help the people of Lui develop more self-sufficiency? How can we help them develop systems so that they won’t have a vehicle “dead in the water” merely because of a broken axle or drive shaft? How can we help their people get education? and how can we make it easier for them to get the parts they need?

This day was Ash Wednesday. Yesterday as our group talked, it struck us that in the Episcopal Diocese of Lui, they don’t pay any attention to Ash Wednesday. We Episcopalians wanted to attend Ash Wednesday services, have ashes imposed, and hear those familiar words: “From dust thou art; to dust returnest.” But it is not observed in Lui – not even in the cathedral.

Others in our group helped me understand some of the liturgical differences between Missouri and Lui. In the American church – and in the West generally – we went through the Oxford movement in the early 20th century, in which the Episcopal Church reconnected with its “catholic” roots and rituals. But many provinces of the Anglican Communion are still based in the very early Anglican roots, which are decidedly Protestant – even evangelical – and anti-liturgical. Partly that’s because the missionaries who moved from the British Empire into the colonies (including Lui) were of this “Protestant” stripe.

When we worshipped in Lui, I was constantly surprised at the liturgical style. They were not merely “low-church” by U.S. Episcopal standards. They were more like Protestants or even Pentecostals. The “liturgy” (such as it was) was completely foreign to me. I did not realize there was such diversity within the churches of the Anglican Communion. And now I am less astonished at the fracture within the Anglican Communion, since the decisions the U.S. church made at GC 03.

It made me sad not to mark Ash Wednesday in Lui. If ever there was a time that I was mindful of the fact that “from dust thou art, and to dust returnest,” it was during those days in Lui. I was sad not to be able to mark that day liturgically in Lui.

Sitting in Buigi on Tuesday, I realized I was starting to cut down on my water consumption. I made a journal entry at 6:00 p.m. and the temperature was still 98 degrees F. I was terribly thirsty. But I also was overwhelmed by the fact that the people of Lui live with this kind of thirst all the time. They don’t have a choice. But I do. I had started intentionally reducing my water intake by that time – because (a) it seemed somehow wrong to drink our bottled water when so many of them are dying of thirst and (b) the less we drink, the less often we need to find the latrine facilities. I realized that day that I was trying, consciously, to maintain a minimal level of dehydration.

Deborah went along on almost all our trips to the outlying villages. And in every village that we visited, there were some people who greeted her especially warmly. Many of these were people whom she had attended as a nurse at the Samaritan’s Purse hospital in Lui. I don’t know how the many, many others had grown to know and love her – but she sure was greeted warmly.

Each time we worshipped in one of the archdeaconries, Bishop Bullen had us introduce ourselves. The visit in Buigi was memorable because the Bishop introduced Deborah as a “Moru-American.” That spoke volumes about how Deborah has lived with them as one of them. It’s clear they have come to love Deborah as one of their own.

Oh, my! I can't tell you how much I would like not to have to reveal what I'll have to reveal here. This is probably the most difficult entry I will post here. We U.S. Episcopalians can tolerate and/or forgive almost all things that some deem to be sin: doubt, divorce, even homosexuality. But the one thing that folks still can get very judgmental about is smoking. OK. I know that. So here it is: I’m a smoker, and I know that may turn-off some readers of this blog. But in case any other smokers think about going to Lui, I need to make this entry for them.

Before I agreed to make this trip, I quizzed the Diocesan staff and past travelers, asking them, “Can a seriously addicted smoker comfortably make this trip?” I knew I could not make an adjustment from my two-pack-a-day habit to going cold turkey. Folks said that it should not be a problem – that they had not seen many Africans smoking, but that was probably because cigarettes are so expensive there.

I discovered that was not actually the case.

I need to acknowledge I’m dropping buckets of sackcloth and ashes on myself for being a smoker. Yes, I know it’s harmful. Yes, I know plenty of people will immediately “write me off” because I’m admitting this habit. No, I have not been able to quit.

This entry is for smokers who may consider going to Lui. The rest of you should just scroll up to the next entry.

Be aware that the Methodist Guest House in Nairobi is entirely non-smoking. No smoking is allowed anywhere within their compound. And if your schedule is like ours, you're going to be there at least 12 hours.

Once I got to Lui, I felt that smoking was o.k. Most of our time was spent out of doors. Of course, I didn’t smoke when we were inside the payuts or tukels. But I felt comfortable smoking outdoors in our compound or when we would arrive in a village after a two-hour drive.

But the exchange with Simon when we arrived in Buigi made me re-evaluate that comfort level. He noticed me smoking and started quizzing me about it. He informed me that Moru women do not smoke, and that the Lui men might therefore be looking at me with puzzlement. [No, I had not picked up on any such reactions.] Simon was also the one who had said that women without husbands or children were essentially worthless. Was this just Simon’s view? or is it a widespread view in Lui? I do not know. But at the time I did take Simon’s words very much to heart. I had not had any sense that my smoking might be a scandal, but his words made me very self-conscious about it.

Maybe the next group going to Lui will have a chance to explore this social norm. For now, I would advise any smokers – especially women – to think twice before visiting Lui.

After the visits in Nideh & Mariba, we went on to Buigi. Like all the other villages, they welcomed us warmly with songs and drumming and a procession that was nearly overwhelming to me.

After the visits in Nideh & Mariba, we went on to Buigi. Like all the other villages, they welcomed us warmly with songs and drumming and a procession that was nearly overwhelming to me.While the clergy were vesting, the rest of us had time to chat. Here are Rebekah (center) and Simon (right).

I had an interesting exchange with Simon, the young man who had been our driver that day and who was coordinator of the Samaritan’s Purse. He was surprised that I was so old (50’ish) and had no husband. And no children. It seemed to me that this was (a) beyond his comprehension and (b) a failing of some sort. This was hard for my U.S. brain to take in. In the U.S., my situation is not so unusual. But talking with Simon in Lui, I gathered it was not merely unusual, but also scandalous.

Later, I told Deborah about this exchange. She and her husband married late, and they have no children. She told me of an exchange with one of the Lui folks, who – when learning of her situation – sadly remarked, “So your family is already dead.”

Wow! When I first heard that comment, I thought it was incredibly judgmental. But then, after living with the Moru, I got to understand it a bit more.

In Lui, if you do not have children/nieces/nephews/grandchildren, then that means you don’t have anyone to grind grain for you, make bread for you, and so on. I guess it means that you are consigned to a life of misery – if you are one of those who lives beyond the average Sudanese age (of mid-40s).

Friday, April 14, 2006

This passage, which he posted yesterday, especially spoke to me:

I think he's said there what I've been struggling to explain to friends about why my time in Lui has touched me so deeply.One of the most used approaches to engaging people with extreme poverty is what I call the Sally Struthers approach. It's the late-night infomercial with sad children with distended bellies and flies circling about their lips and Sally Struthers bemoaning how terrible it is and won't you please send money to help.

It's not that it isn't terrible. It's not that on some level it's very important for people to see how terrible it is. But we shouldn't help out of a sense of guilt or out of a sense of repulsion. We should help out of a sense of how we are bound together -- out of a sense of the deep joy, the deep experience of life in Christ that comes from solidarity with the poor.

Sabina Alkire, the amazing priest-economist who co-authored What Can One Person Do: Faith to Heal a Broken World, says: "The alleviation of material suffering in the world and the spiritual renewal of the church go hand in hand."

Sabina is right. Sabina understands Jesus words. The extreme poverty of the developing world is also the extreme poverty of the developed world. They are inextricably related. Because as we allow -- and even cause and perpetuate -- extreme poverty in places like Sudan and Tanzania and Nicaragua and Pakistan we deeply impoverish ourselves as well.

We impoverish ourselves because the only way to perpetuate systems of extreme poverty is to distance ourselves from their victims. We cannot leave people in poverty if we believe that they and we are one. So as the poor suffer materially, we suffer spiritually.

Wednesday, April 12, 2006

Since being home for almost a month now, I find there are small (or maybe not so small) things that I realize I did not know about or understand. For me, it was so easy to get caught up in the day-to-day and moment-by-moment activities and conversations that I failed to process some of the “big picture,” and only recognized these gaps when I got home. If I were going back to Lui this month, these would be the questions I would explore with people. And I offer them partly to the next group because sometimes it’s hard to know what to discuss with people, and perhaps some of these can become “discussion questions” on your trip.

Infrastructure. I found it astonishing, as I learned more and more about how much infrastructure is not present in Lui: no system for tending to roads, no postal service, no communication infrastructure. One of the most striking to me, though, was that there seems to be no structure for registering land ownership. Apparently, if someone wants to settle on a parcel of land, s/he (but mostly he) goes to the Bishop and asks permission to stake out that parcel. There seems to be nothing like our Recorder of Deeds. In fact, there seems to be no civil authority whatsoever for registering “ownership” of land. But maybe this is just because I did not ask the right questions. I would be interesting in learning more about this. I gathered that one goes to Bishop Bullen in these cases and asks for a certain parcel of land. Is that true? And, if so, does he maintain some sort of “land registry”?

And that ties into a broader issue. My perception was that there is no civil government, no civil authority. My perception is that those structures – if they ever existed – were destroyed in the decades of civil war. We learned that the Episcopal Diocese of Lui was just about the only structure that continued to function through the period of the wars, and they are thus functioning as the “civil” authorities as well as the ecclesiastical ones. I would like to understand more about that.

Evangelism. As I’ve observed, the Bishop is confirming dozens (hundreds?) of people each year in Lui – ranging from children to senior citizens. I would like to learn more about where these converts are coming from. I assume most of the adults are being converted from the older, animist religions. How are they reaching them? What kind of confirmation process do they undergo? Do they undergo the kind of weeks-long classes that our folks endure?

Indigenous Religions. I’ve seen the statistics that characterize southern Sudan as roughly 20% Christian and 70% “animist.” But I never got a chance to explore what those animist religions are. I’m completely ignorant about them. I hope somebody might shed some light on that, and might explain to us how Lui Diocese reaches out to those people.

Ordination. After I got home, I realized I was not at all clear about what criteria/process they use for ordination. Here, we have a very rigorous, structured “discernment process” through which one may move to the diaconate and priesthood, and we have many requirements regarding education and assessment. I realize I’m not at all clear on what the process is in Lui, but it seemed much looser. I’d like to know more about the process.

And I would like to understand more about the role of women. There are women whom we called “Mama Margaret” or “Mama Janifa.” But I realize now that I was not at all clear on their canonical status. Are they priests? Does Lui ordain women to the diaconate? to the priesthood?

Water. When I gave my “Reflections on Lui” program at Grace/Jeff City last week, folks asked lots of questions. One that stumped me regarding their lack of safe drinking water: Why don’t they just boil their water? When we were in Lui, I noted children drinking unspeakably filthy muddy water. And I understand that many of their most devastating diseases are water-borne. But for some reason, while I was there, it never occurred to me to ask what, if any, steps they can take – or what steps they know to take – to purify their water.

Carnivore or vegetarian? This week I saw a new entry from Deb that mentions the folks in Lui are carnivores. My impression had been that they kept their goats and chickens for the products they generate, rather than eating them. I had understood that they mostly ate grain-based foods and vegetables (when available), but that’s not what I’m seeing from Deb’s blog. I’d like to understand more about what the people of Lui generally eat.

Marriage. During one of our truck rides, I could hear part of a conversations between the Missourians and the Moru about how marriage occurs in Lui. There is discussion in the U.S. about the distinction between civil marriage and "the blessing of a marriage" in our church. I gather that the Moru keep this distinction much more than we do -- that they distinguish the civil from the ecclesial elements -- and that much of it is related to economics. I would like to understand this better.

Women’s sanitation. One woman who attended my “Reflections on Lui” program at Grace last week had friends who made mission trips into the developing countries, and one of the things they observed and were able to help with was how women deal with their menstrual periods, since they lack the kind of sanitary products U.S. women use. That group was able to provide products to those women. She asked me to inquire about what kinds of issues the women of Lui might have, and whether we might be able to offer any assistance there.

When I first arrived in Lui, I saw all those children and adults with flies settled on them. It reminded me of all those heart-rending “Christian Children’s Fund” TV infomercials I see late at night. Lord help me, I dismissed them. I said to myself, “Why don’t those people shoo the flies off themselves?”

But a few days after being in Lui, I suddenly recognized a weird thing had happened to me. I felt flies settling on me, and I did not swat them off. Yes, if they landed on my nose or mouth, I would swat them. But most settled on my head or face or arms or legs, and I did not trouble them.

I was appalled when I realized this. “WHAT? is going on???” I asked myself. And then I realized. When temperatures are exorbitantly high and you need to reserve all your energies for the really important things, swatting flies just doesn’t rise to the level of a Really Important Thing. It’s really o.k. if flies want to harvest some of the sweat off your arms or legs or belly. It’s not a value judgment.

I will never look at those late-night infomercials the same way again.

[Somehow, this title reminds me of the phrase from my childhood: “Running with Scissors.” Maybe both are fundamental fears!]

Frankly, I’m surprised that this was such a big issue for me. It surely should not have been! But having to eat without utensils in Lui was difficult for me.

Before our trip, people warned me that no eating utensils are available when you’re eating in Lui. It did not concern me at the time. After all, I had grown up (Southern child of the ‘60s) eating ribs and pork chops and fried chicken by hand. I envisioned Lui the same way.

What I did not envision was that we would be eating rice and beans and very drippy foods by hand. I did not envision that we would be eating foods that would create a lot of liquids.

Thank heavens! The people in Lui have purchased spoons for the guest compound. So when we were in the Lui guest compound, we had eating utensils – which were especially helpful when we were eating rice and beans and greens.

But that’s not the case when we went out to the remote villages. There, they have no utensils. We were served most generous meals – chicken, goat, fish, breads, gravies, sauces.

I’ll confess it: I chose my foods based on which ones I felt comfortable eating with my hands.

WHY was this “eating with hands” thing so powerful and so determinative for me? I’ve often asked myself this, since coming home from Lui. It wasn’t about “manners” or sanitation. I think it was something much more primordial. Growing up as a child in the U.S. when I did, there was one powerful message from our parents: “Being a big girl” meant “eating with utensils.” Maybe that’s part of the reason this was so important to us.

And let’s talk napkins! For sure, if there are no eating utensils, you can bet there are no napkins – whether paper or lovely damask. When my hands were drippy sloppy with beans and gravy juice, I missed napkins big-time. But I got lucky: When I was packing, something told me to take bandanas with me. And I took them out to the villages with me every day. I sure was happy to have them, when my hands were dripping.

While I’m feeling very Western and self-indulgent in those confessional comments, I also want to add these: Every time we were welcomed into a village and escorted into a payut to eat, someone would greet us with a basin of water and soap so that we could “wash up.” And – always! – after the meal someone would come around to all of us again to wash our hands. The Moru were very careful about cleanliness and washing-up. I’m not impugning them. It’s just that we – or, at least, I – have developed these really anal, fastidious habits... which our culture and our resources allows us to maintain. But those are not the ways of the Two-Thirds World. In fact, I came to see, our ways are actually the weird ones. I freely and repentantly acknowledge that my fastidiousness were rather “warped” in that setting.

Tuesday, April 11, 2006

On one of my first days in Lui, I noticed that a toothbrush was stuck in the grass thatch just above the tukal entrance. And while I was inside one of the tukals, I noticed another toothbrush stuck in the grass roof above me. I asked Peter, the man who cared for us in the compound, what that was about. If I understand correctly, here’s what he said.

The Moru of Lui don’t much have access to "toothbrushes" per se. Instead, they would grab a small twig in the morning and work it around their teeth during the day -- working it or sucking on it as the inclination led. When they were finished with this twig, they would just stick it into the thatch as they returned to their tukal.

Then they got access [I’m not sure how – probably from visitors like us] to toothbrushes. But they would keep the same habit: work it around during the day, then stick it in the tukal roof when they were finished with it.

And thus I saw these tukals – which look like structures from the middle ages – with an OralB toothbrush stuck in the thatch roof here and there. Truly, delightfully anachronistic!

Monday, April 10, 2006

We arrived in Nideh and visited with them briefly. But the Bishop wanted us to drive to Mariba, so we took a hasty departure.

I wasn’t entirely clear on why the Bishop took us away from Nideh so quickly to visit Mariba.

The sign when we entered Mariba (pictured above) also designates it “PHCU." That stands for Primary Health Care Unit. This means this is one of the Samaritan’s Purse hospital’s outlying units – a place where people can receive basic medical attention.

I’ve tried to talk about how primitive the roads are. Perhaps this shot will help. This is the road leading into Mariba. Can’t see a road? Maybe that’s because the “roads” are barely discernible. The opening between the trees here (just left of center) is what passes for a road.

I’ve tried to talk about how primitive the roads are. Perhaps this shot will help. This is the road leading into Mariba. Can’t see a road? Maybe that’s because the “roads” are barely discernible. The opening between the trees here (just left of center) is what passes for a road.When we arrived in Mariba, we quickly saw that there were virtually no “permanent” structures in the village – that is, none of the “mud” buildings we had in Lui. Every structure in Mariba was a newly-built one made of grass bundles, like these.

This reminded me of the earlier comments I had heard. People build of grass when they have little faith in the peace; they build in mud and brick when they believe the peace will hold. Moreover, they build of grass when they don’t fear they may have to run for their lives from attackers. As somebody said, in a grass hut you can flee in any direction, but you only have one door from a mud hut.

This reminded me of the earlier comments I had heard. People build of grass when they have little faith in the peace; they build in mud and brick when they believe the peace will hold. Moreover, they build of grass when they don’t fear they may have to run for their lives from attackers. As somebody said, in a grass hut you can flee in any direction, but you only have one door from a mud hut. Here several of our group view one of the burned-out tukals. To my ignorant eyes, this “merely” looked like the site of a tragic fire. But as Bishop Bullen walked us around the village, he explained what had happened. These people had been burned-out of their village. The Dinka people had come in, destroying the homes of the Moru. The Moru had seen family members – those not fast enough to run into the bush -- hacked to death. They had lost everything they owned: cooking utensils, clothing, agricultural implements, you name it! I think this is where it hit me – how the people of Lui had lost everything.

Here several of our group view one of the burned-out tukals. To my ignorant eyes, this “merely” looked like the site of a tragic fire. But as Bishop Bullen walked us around the village, he explained what had happened. These people had been burned-out of their village. The Dinka people had come in, destroying the homes of the Moru. The Moru had seen family members – those not fast enough to run into the bush -- hacked to death. They had lost everything they owned: cooking utensils, clothing, agricultural implements, you name it! I think this is where it hit me – how the people of Lui had lost everything.I don’t know about other people. But as I walked around the village, I was increasingly appalled by how this travesty could have been done. It was beyond breath-taking.

After we had walked around the village, we settled into a formal greeting. But there was no structure in which we could meet -- no nice, cool payut in which we could gather. There were no basins in which women could bring us cool water to wash our hands. There was no food that they could give us. There was only a tree, in the shade of which we gathered and listened to them sing. And we prayed. And some of us cried. What else could we do??

This is the priest who remains in the village: Pastor January.

As we moved away from the village and toward our truck, I saw Archdeacon Robert talking with Bishop Bullen, then he handed some money to Father January, so he could buy food in the Lui market for his parishioners. It was the most we could do in that brief visit, and it felt so meager. And yet I bet the rest of the group was praying, as I was, that God would multiply it and use it to sustain them through the long coming weeks.

Piling back into our Jeep at the end of that brief visit, it hit home for me. I was going to return to my comfortable life in the U.S. after a few uncomfortable days in Lui. These people were left there to eek out a living after being attacked by “fellow Christians.” Whatever “deprivations” I thought I had suffered in Lui to that point, I think that’s the moment where God put all of them into perspective for me.

After what feels like days and nights devoted to writing here, I've been "off the blog" for a while now. My home parish scheduled me to do a program for our parish, in which I could share my experiences of Lui. We made it a soup supper and program to follow our last Lenten evening prayer service. The program was Thursday, April 6. I was incredibly gratified that our parish -- with an average Sunday attendance of about 140 -- had about 50 people show up on a Thursday night for the program on Lui.

From the very beginning of this experience, when the Diocese asked me to go to Lui and I began talking with folks in my parish about that opportunity, I have felt an intense level of support from my parish. I continue to be moved beyond words at their support of the relationship with Lui, and support of me. That support was abundantly clear on Thursday night. They were delightfully and patiently interested as I went on and on and on and on and on about the experience. (Those of you who know me will understand that I am not "disabled" when it comes to the ability to go on and on and on and on ....) Thank you, Grace friends; you're the best!

On Tuesday, I again accompanied the group visiting the archdeaconries. On the road to Nideh, we were stopped by a team of people contracted by the U.N. to remove the mines from the roads. During the long civil war, the Khartoum had placed mines all along the roads, and now the deadly heritage of that war is the desperate need to identify and remove all those mines. I have already written about that encounter at Thoughts on war & security. Here’s the scene we saw ahead of us, when the South African de-mining crew started alerting us to stop our vehicle.

The guy in the center of the photo is head of the crew working with the South African company the U.N. had contracted to do the de-mining operation.

I’ve already written about this encounter at Thoughts on war & security. So I won’t repeat it here. I’ll just add these couple of reflections.

The men in the de-mining crew were only coming from Juba (in the east), which I think is a mere 75-100 miles from Lui. I’m pretty sure that Lui and Juba are no more than 100 miles apart – which would be very close, according to our culture and with our roads. But there in southern Sudan, these towns were many days apart.

But the way their group and ours talked, you would have thought we had been living and working a thousand miles apart. Some in our group were asking the South Africans about the rumors we had heard that cholera was beginning to break-out in Juba along with the coming of rain. With equally fervent interest, the South Africans traveling from Juba were inquiring of us whether the peace agreement was holding in Lui. This reminded me of how it must have been in the “wild west” of the 19th-century U.S., when travelers would meet at an inn, having no infrastructure of television, radio, or newspaper news. For the most part, in Lui news travels only at the speed of a fast-walking man. A few people travel by bicycle and a rare few travel at the speed of a bicycle. And apparently some news travels with drums beating out a message from village to village.

One of the priorities in the companionship agreement between the Diocese of Lui and the Diocese of Missouri is that we will assist in building infrastructure to assist Lui with communications within Lui, between Lui and its Nairobi office, and between Lui and Missouri.

Maybe it was that day – observing Westerners eagerly exchanging news alongside a sun-parched road – that I realized how vast is the distance between our U.S. conceptions of infrastructure and the basic, fundamental needs for communication. It’s going to be a long, hard slog, I fear.

Tuesday, April 04, 2006

Confirmations

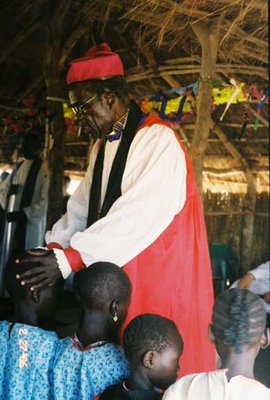

In each archdeaconry we visited, Bishop Bullen did confirmations. There were roughly 20 or more people in each village – ranging from children to senior citizens.

I understand Bishop Bullen made his Episcopal visitations and did confirmations at Advent – only 3-4 months ago. And yet here we were – just 2 months later –making another round of confirmation visits and confirming 20 or more people in each small archdeaconry. How is the Sudanese Church bringing in so many people so quickly?

Without a doubt, the Christian church is growing in Lui. I wonder how they are achieving this evangelism. And do they have catechism classes? Are these folks coming in from “the bush” to accept Christianity? How are they achieving such massive numbers??

Starting Tuesday (28 February), we heard that there are suspicious outbreaks at Samaritan’s Purse, which might be cholera. This news has folks worried.

On one hand, people in Lui were praying for the rains to start. If the rains start, they can begin planting crops.

But there’s a downside too. When the rains begin and the rivers begin to flow, that also means that cholera begins to spread.

It feels like nothing in Lui is an unmitigated “good news” announcement. It seems like everything – like this “good” news of the rains – is accompanied by “bad news” or at least a caution.

The Moru people have a tradition that I think we used to have – they have one name at their birth, and another at their baptism. One thing that really struck me as we talked with the Moru was their wonderful baptismal names. My two favorites were the names of two boys who hung around our compound day after day: “Repent” and “Free.” I wonder what experiences made their parents choose these baptismal names.

My copy of Episcopal Life arrived today. It has a good article, ”Seeking Ways to Help,” that describes a relatively new organization of Episcopalians. According to the article, the American Friends of the Episcopal Church of Sudan (AFRECS) exists to encourage advocacy and prayer about Sudan, raise awareness of dire needs in the country, and provide a forum for people to compare notes as they separately try to strengthen southern Sudan and the Episcopal Church of Sudan. It includes many U.S. parishes and dioceses who have partner relationships with Sudanese dioceses, as well as Sudanese living in the U.S.

AFRECS held a national meeting in California during February, and I hear that our Archdeacon Robert attended that meeting. I gather this group may be an important source of information and concerted action. The AFRECS website may be useful for Episcopalians wanting more in-depth information, and it has a good set of links.

As I understand it, AFRECS is trying to tackle some of the big, thorny issues that complicate our work with the Church in Sudan. For example, I learned while in Lui that it is illegal (under U.S. law) for us to send money to Sudan. That's because the U.S. government has determined that the Sudanese government in Khartoum is a state sponsor of terrorism. Unfortunately, that declaration also complicates our work with the folks in Lui who are not functionally associated with the Khartoum government.

Let's hope this organization will give much-needed support to our diocese's work with Lui.

Monday, April 03, 2006

The drive to Kedibah was miserably long, and – after a very long hot day – the ride home from Wandi was even more miserably long. When we piled into the truck to leave Wandi, my tired body (and tired and bruised butt) was dreading the long 2-plus hour drive more than I can describe.

You know how it is when you’re on a miserably long trip. You just set your jaw and steel yourself to the long misery. I think that’s what we were doing. It certainly was what I was doing. We were too hot, tired, miserable, and overcrowded in the miserable back of that truck. On the trip out to Kedibah, there had been much conversation. But on the trip home that day from Wandi, the conversation got less and less.

But then something weird happened. I don’t know who started it. But somebody started singing. And some people joined in. Mind you, half of us were Americans and half were Lui. Though all Anglicans, we don’t really have a prayer book in common, and we certainly don’t have a hymnal in common. But we found common music. I don’t know how, but we did. Partly, we found hymns that are in both our hymnals. The folks in Lui just love ”Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus” and ”What a Friend We Have in Jesus,” -- and just enough of us Missourians knew those songs that we could sing along. And we all knew ”Amazing Grace” -- heck! we even knew most of the verses! – along with ”Jesus Loves the Little Children”. Then we resorted to campfire/Girl/BoyScout songs like “If You’re Happy and You Know It” -- which included several extemporaneously-fabricated verses like “If you’re happy and you know it, say ‘Hey, Bish!” in honor of Bishop Bullen sitting in the front seat and enjoying our singing. Then we remembered that we had seen “Kumbaya” in the Moro hymnal. Yes, Kumbaya! And sang many verses of it. Then we moved on to civil-rights-era songs like ”We Shall Overcome”, to which we added wonderful verses like “We’ll rebuild Lui.”

This was like the most fun memory you ever had of a family sing-along! The minutes and miles passed without a thought. One person would think of a song, then another would come up with the next song. And the Moru are very fond of their percussion. Rebecca had a “gara” [gourd] and was using it. After a while, Deborah remembered she had a pill-bottle, and she started shaking it – and, by crackies! it made a very fine percussion instrument too. [By the light of the next day’s sun, Deborah learned that she had pulverized those pills to a fine powder!]

This miserably exhausting day had gone on very, very much longer than any of the other day’s outings. We knew that we had left Rick and Father Bob back in Lui, and the closer we got to Lui, the louder and more happily we sang! When we saw the Lui gates, the dozen of us were singing at the top of our lungs! I don’t know about the others, but I certainly was aware of the hope that Rick and Bob would hear our singing and know we had had a wonderful day and were coming home happy.

So our driver pulled into the compound and stopped, and we started piling out of the truck. Our faces were just jubilant with joy. But I could see that Bob and Rick and Gordon’s faces were not – not at all! In fact, they looked distraught.

It was later that Rick and Bob explained what had been happening there in the compound. They had been very, very worried about us. It was after 9 p.m. when we got home – two hours after dark. There are no phones that we could have used. Waiting with them was Gordon, one of the Lui priests. After minute passed minute, and finally hour passed hour, they apparently became more and more concerned that something bad had happened. Then they heard the sound of our singing. And Rick and Bob got excited. But Gordon was crestfallen. And Gordon explained to Rick and Bob that that’s how the Moru bring home their dead. They "sing them home."

Yes, that’s right! The joyous sounds we were making -- which we meant to signal our friends that all was well -- told Gordon that we were carrying home a corpse!!

So now I can understand why, when we came piling out of the truck all happy, Rick and Bob and Gordon were looking so distraught! We had found resurrection in the midst of misery. But they were waiting to see what corpse we were going to haul out of the truck. WOW!

Culture. Cultural differences. You folks who are going to Lui, get ready to have all your cultural assumptions challenged. Ours certainly were, when we ended that day.

Yes, bird!

On Monday, we visited the war-torn village of Kedibah, then visited Wandi. The Wandi visit was “typical” – a greeting into the village, worship service, then a meal with them. Then – as was typical of our visitations – we would all join together in a circle under a big, shady mango tree, and they would sing to us.

Every time, I was mindful that they had just fed us with food they could not afford – with food that they gave to a few of us, when dozens of them needed it desperately.

But on this day something very out-of-the-ordinary happened. As we gathered in that leave-taking circle, an old woman sang in the middle of the circle, and she had something in her hands. Now, it often happened that an old woman moved to the center of the circle and sang, but never had I seen one of them with something in her hands. This woman had something her hands, and it was in a sort of “Baggie.”

Then – as she moved toward the end of her song – she began dancing toward Archdeacon Robert. And as she ended her song, she placed this “offering” into Archdeacon Robert’s hands. Initially, I was puzzled. It sort of looked like soil. Then I thought maybe it looked like seeds. Then I saw its feet protruding out the bottom of the plastic bags and realized, ”It’s a bird!”

I don’t think our poor Archdeacon knew what to do with it!

What struck me was that these people were starving to death. And yet they found a bird and gave it to us – to we who were being so incredibly well fed! The generosity of this gift was awesome to me.

By the way, to your naturalists and animal-lovers out there: No, I do not know what this bird was. It was certainly not a chicken. The people of Wandi said it was a “Cara” [pronounced somewhere between “cara” and “cadah”]. It looked like it was a bird in the quail family.

The bird met its maker on our long drive back to Lui, and we gave it to one of the Lui women when we got home to the compound.

In each of the archdeaconry meetings, Archdeacon Robert explained the terms of the covenant relationship between our diocese and Lui. In one of these sessions, it occurred to me: one of the promises is that we will send them a complete financial statement of our diocese’s spending. We will show them how we spend all of our money. How we spend all of our money! I’ve sat in diocesan conventions in which we approved our budget and it made perfect sense to me. But sitting there in Wandi, I suddenly wondered: How will our budget look to them? We fund our staff, our utilities, our convention, so many things that we accept as crucial to our infrastructure. But … how will our budget look when it’s being reviewed by people who are starving to death?? I fear it will look very self-indulgent. Are we about feeding the infrastructure? or are we really about mission??

A focus of our mission was to visit each archdeaconry [These are the equivalents of our Convocations in Missouri, or deaneries in some other parts of the church.] Archdeacon Robert was to explain to them the covenant agreement that our diocese and theirs had negotiated and to invite their comments on it. We did indeed receive many passionate comments, but I am not going to mention them here, since I think these are supposed to be addressed by our Bishop and diocese. All I’ll say here is that the people of Lui were pleased – very pleased – to see us among them. But they were also skeptical. As one man in Kedibah said, “The words are there, but the actions are not yet seen.” That broke my heart. We must soon make our actions match our words!

I was struck by the Lui custom of serving “first,” “second,” and “third” coffee. It was a puzzle to me at first. And I consider myself a serious coffee-drinker. For you other coffee-lovers, I offer this explanation.

I gather that they must put the ground coffee into one vessel, and then they offer the first serving. The “first coffee” is the strongest brew. It’s a stand-your-hair-on-end brew!

Then they and the coffee pot will disappear, then they come back offering “second coffee.” I gather this is where another batch of boiling water has been added to the coffee grounds, so it’s not as strong as the “first coffee.”

Then they disappear a while and return with “third coffee.” This is the weak coffee that my family typically served.

You’ll typically be offered sugar with you coffee. But there is no milk – much less cream.

Deborah has warned us of the risk that any of us will think our visits and experiences are “normative,” whereas there are many variances from village to village. While I recognize that’s true in the particulars, I think there are also some commonalities that future missioners can anticipate.

First, there’s the welcome to the village.

In every village, they met our truck on the road and paraded us into the village, to the accompaniment of singing and drumming. We always stopped the truck, and more or less of us would join them in this parade. [In this photo, Sandy is visible at the extreme right. Here, and on every village I saw, the Lui folks carried the generic Christian flag at the head of the procession. Personally, I'm not enamored of that flag. I sure wish we could get Episcopal/Anglican banners to them!]

In every village, they met our truck on the road and paraded us into the village, to the accompaniment of singing and drumming. We always stopped the truck, and more or less of us would join them in this parade. [In this photo, Sandy is visible at the extreme right. Here, and on every village I saw, the Lui folks carried the generic Christian flag at the head of the procession. Personally, I'm not enamored of that flag. I sure wish we could get Episcopal/Anglican banners to them!]

Then there would be formal welcome remarks. The Bishop always pronounced a welcome. And there were typically also remarks from the Archdeacon, a tribal elder, or other dignitaries. And there were prayers. We were never asked or expected to speak formally in this ceremony. [In this photo, the man in the center (with the t-shirt) was the official representative of the SPLA/SPLM -- the new military/government presence created in the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in January 2005. I sense he had much authority.]

Then we would be led into a payut or tukel. This gave us a time in the shade where we could cool down. Usually, one of the people from the village would come with a basin of water to wash our hands.

If there was time enough, we were offered something to drink – either hibiscus tea or coffee – and sometimes a bit of bread also. In my experience, only an “inner circle” were included in this respite – only us travelers and the Bishop and clergy accompanying us. It seems this was viewed as relatively “private” time.

If there was time enough, we were offered something to drink – either hibiscus tea or coffee – and sometimes a bit of bread also. In my experience, only an “inner circle” were included in this respite – only us travelers and the Bishop and clergy accompanying us. It seems this was viewed as relatively “private” time.All the visits we made were to archdeaconries, where we were going to worship with the people and where the Bishop was to do confirmations. So the next step was that all the clergy (including Mothers Union) would move into another structure to vest.

In every village, there would come a moment where all the clery would come out for the processional. And every time, I got teary-eyed. Here is one of the many processionals we saw. This one is particularly special because Mama Janifa is smiling and waving. (She did not do that a lot!)

Then we would worship together. As I’ve mentioned already, all of us “honored guests” were seated in special chairs in the chancel.

At a certain point in the service, all of us guests were directed to introduce ourselves and offer greetings. This is very stylized. Here’s how it went for us. The Bishop would ask us to come forward and greet the people. One by one, we would stand and move to the edge of the chancel. There was a somewhat formulaic greeting, along the lines of, “I greet you in the name of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.” Then we would tell them our name and say we brought greetings on behalf of our home parish. Sometimes some of us would also say a little more – or a lot more – by way of greeting and compassion! One odd (to me) thing about this was getting used to having a translator working with me. I had to get into the habit of saying just one phrase at a time. And I had to get used to the fact that the people of Lui would applaud after almost every line I spoke.

After the service, and the greetings, we would be escorted to the payut again to have a meal.

In our visits, we also had meetings with the clergy and village leaders. These meetings were generally before the meal. (

I took this photographs from the chancel. You can see Archdeacon Robert and (at right) Sandy in the foreground, and the many people who attended the meeting in the rest of the photograph.)

I took this photographs from the chancel. You can see Archdeacon Robert and (at right) Sandy in the foreground, and the many people who attended the meeting in the rest of the photograph.) At the end of the worship and meetings, we would all move back out toward our truck, and all the people of the village would gather around us. They would sing to us, then we would have prayers, then load into the truck. Then they would sing us on our way.

Every time we departed a village, those faces would haunt me. I could see it in their faces – the question, “Will they remember me once they return to the comfort of the U.S.?” They would sing, and reach their hands out to us. And I would feel another piece of my heart being left behind.