Friday, March 31, 2006

The Moru are an agricultural people. They farm. Increasingly, they are Christian. During the civil war, one neighboring tribe – the Dinka – also came under fire from the northern government. The Dinka are “ranchers”; they raise livestock, primarily cattle. The Dinka were displaced during the war, and they sought refuge among the Moru. The Moru took them in, I am told.

I am told that the Moru suffered some hardships under this arrangement, as the Dinka cattle knocked down fences and ate the Moru crops.

Then the peace agreement came, and finally – in the fall of 2005 – the Moru told their Dinka guests it was time to go home. But – I am told – the Dinka observed that their livestock had never been so fat and healthy. They did not want to leave. Instead, they went on the attack. Or so I am told.

We are told this: Last fall, the Dinka began burning Moru homes and villages, and slaughtering the Moru people, in order to take over the land. We heard story after story about this – about how the Dinka would descend on a village and kill everyone not fast enough to disappear into the brush. We certainly saw the resulting carnage: burned homes and villages. And we heard tales of people who saw and heard their family members slaughtered.

I’ll be posting photos of these villages here, as we visited several of them.

Meanwhile, I have this observation. Our Moru friends regularly talked about those atrocities. And they spoke of it with tremendous grief. But they did not speak of it with anger or vengeance. The Moru were betrayed and murdered by their “Christian” friends – people who had lived alongside them for quite some time. And yet the Moru do not – even now – speak out of vengeance against the Dinka. Time after time, what I heard from them was a sense of grief and sorrow.

I cannot help but contrast this with Americans in general – and U.S. Christians included – after the September 2001 attacks on our country by “strangers.” What is it that makes our nation so angry and vengeful against those strangers, when the Moru – attacked and murdered by “friends” – can behave with such restraint?

This theme will recur in several of the later entries, so I’ll highlight it here. I hope I have the facts relatively accurate. In a place with no newspapers or “documentation” that I could discern, one must simply rely on the stories one is told. This is one of the sadder ones.

Over the past 50 years, southern Sudan has suffered war of one type or another for 40 years. As I understand it, most of this has been a result of the Arabic and Muslim northern Sudanese attacking the African and animist/Christian southern Sudanese. Or, viewed another way, it’s been the southern Sudanese fighting for self-control against the north.

Finally, in early 2005, a peace agreement (the Comprehensive Peace Agreement or “CPA”) was agreed-upon by both parties. As I understand it, it provides a five-year (or is it 6-year?) period during which southern Sudan under the SPLA/M will exist fairly autonomously. At the end of that period, there will be a vote throughout Sudan that will decide whether southern Sudan retains its autonomy or comes back under more direct national control.

Meanwhile, various groups in southern Sudan have been “united against the common enemy,” and many, many people have been displaced, driven from their homes and lands.

People in Lui look up to Father Joseph Phillip, dean of the cathedral in Lui. One of the reasons is that – despite many bombings – he refused to leave his cathedral in Lui. While people were being murdered and their homes destroyed, he remained in Lui to keep the church operating there. And it wasn’t just other people being attacked. When we arrived in Lui, I noticed this one derelict/falling-down building and inquired what it was. And I was informed it wasn’t a “was.” It’s an “is.” It is Father Joseph Phillip’s house. It’s still his house. It’s been bombed and assaulted. But he’s still living there.

One of Rick’s jobs while we were in Lui was to inspect Father Joseph Phillip’s home to determine whether it was even habitable. It had been bombed so often, and had so many crumbling/leaning walls that – at first – I did not even recognize it as a home. I thought it was one of the “destroyed places.” But he is living in it, as he has continued to do all along.

I understand the Bishop experienced similar destruction. If I understood correctly, one of the sites we visited was the place where his home had once stood. I heard various stories about how many times he had endured bombing of his home.

I cannot even fathom the courage it must take to do this. We speak of Christians being “under assault” in the U.S. What a joke! These Lui Christians were bombed, attacked, and beaten. And yet they held their ground.

I noticed that the Cathedral in Lui had this funny roof. It was fashioned of corrugated metal, and looked mostly silver. But it also seemed to have a green paint in some sections. I learned why. During the civil war, the Khartoum government realized that schools and churches had shiny corrugated-metal roofs. So they sent their planes to bomb them. The shiny silver roofs stood out vividly, making them easy targets. Awhile into the war, the diocese realized this, and they painted the roofs green, in hopes they would blend into the surrounding vegetation.

Just before our group headed to Lui in late February 2006, I heard the people of Lui were suffering from major drought and shortages of food. But I also heard that – thanks be to God! – the mango trees were beginning to bear fruit. Indeed they were, when we arrived. I thought surely this was a good thing – as it would give them food and nourishment.

The mango trees in Lui are a thing of beauty. They are huge, sheltering shade trees. It feels much cooler under the spreading branches of the mango than it does in the sunshine outside. And the fruits hang down so deliciously.

I saw many, many people – and especially many children – using branches or any long implement to knock the mango fruit off the trees. And I assumed this was a good thing. But now I am informed that they were harvesting the mangoes before they were ripe, and that people are becoming sick as a result. People who are dying of hunger and thirst are harvesting the mangoes to feed themselves and provide a source of liquid, and this is killing them?? How can this be? – when we can afford to spend $3 and up for coffee and have so much food that we throw it away day after day?

I saw many, many people – and especially many children – using branches or any long implement to knock the mango fruit off the trees. And I assumed this was a good thing. But now I am informed that they were harvesting the mangoes before they were ripe, and that people are becoming sick as a result. People who are dying of hunger and thirst are harvesting the mangoes to feed themselves and provide a source of liquid, and this is killing them?? How can this be? – when we can afford to spend $3 and up for coffee and have so much food that we throw it away day after day?I am speechless at the injustice of it!

Father Bob has talked about how well we were fed when were in the Lui compound – and we were! There was always more food than the five of us could or would eat. It always bothered me to realize how luxuriously we were being fed, especially recognizing how our abundance compared to our hosts’ scarcity. The one thing he didn’t mention – but which I think we all realized – was that when we had those meals in the compound, we were aware that any of our leftovers would go back to the Lui folks to feed their families. Personally, at every meal, that motivated me into a mind-set of “how little can I eat?” rather than “how much do I need?”

Things were somewhat different when we visited the outlying villages. Here, even before I begin my narrative, I am mindful of Deborah’s counsel. When you travel around Lui, you tend to think your experience is normative. If you observe something, you think that’s how it always is. As she said, it’s like the oft-cited story of the blind men touching the elephant; each one thinks his perception is The Whole Truth. So I preface my remarks with the recognition that other people have had and will have different perceptions and different realities.

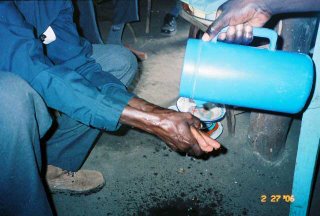

This was a constant in my experience in the outlying villages. Each time we arrived in a village, we were ushered into a tukel, and the local people washed our hands. Hearing about this custom before our trip, I thought “How quaint!” But it’s not merely quaint and it’s not merely symbolic. If you travel from one village to another, you are hot and sweaty and filthy! It’s dry and dusty, and you’re covered with dirt and sweat. You might not “need” your hands washed, but you sure do wish for a chance to have them washed!

Here, Archdeacon Robert is getting his hands washed in the village of Kedibah. Bishop Bullen is looking-on in the background.

Here, Archdeacon Robert is getting his hands washed in the village of Kedibah. Bishop Bullen is looking-on in the background.It didn’t take very long to connect this experience to the New Testament stories of Jesus – of how he arrived in a village, and a woman washed his feet with perfume, and of the Maundy Thursday story of his washing the disciples’ feet. Suddenly, those stories sprang to life. They were not “symbols” of anything when those events took place. They were just dirty, practical reality.

On our trip, sometimes we had time to have a meal with the local people when we arrived in a village. Other times, we were running so far behind schedule that we had to get to church quickly and have a meal afterwards.

In either case, the drill was pretty much the same.

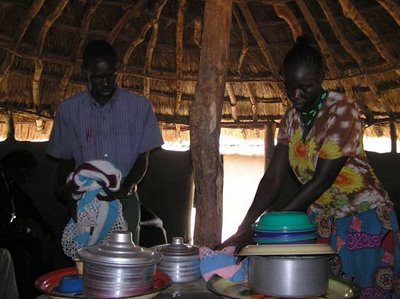

People would wash our hands. Then people (usually women) would bring the food into the tukel. Some people had the experience of seeing them coming into the tukel on their knees. I did not have that experience. Usually the people who brought the food were those (usually women) who had cooked the food. Then they would offer the blessing. Every time I saw this ritual, the people who delivered the food and prayed the blessing did so on their knees – while the rest of us (the Bishop and his staff of Lui clergy, as well as those of us visiting) sat in our comfortable chairs. It was a humbling moment. Then they would remove the covers from the food.

This is a typical “spread” in the villages. There’s rice (at the extreme left) and beans (at the extreme right). In the foreground is the sorghum-based bread that Father Bob has written about. This village was fairly close to a river, so they also provided fish (in the bowl at the upper left). In some of the villages, they also offered chicken or “meat.” Child of the beef industry that I am, I somehow thought that “meat” meant “beef.” It was only after I got home – and realized I had not seen a cow in those 12 days – that I realized “meat” translates to “goat” in Lui. I ate plenty of “meat” in Lui – and enjoyed it!

Father Bob has written about the wonderful wheat bread we often had in Lui and mentioned the sorghum-based bread we often had in the villages. He spoke of the fact that these were “rare treats.” I did not understand why they were such rare treats until I began to grasp the labor involved in making this bread. Start with this: The women in Lui can’t just run out to Schnuck’s and pick up a pound of flour. They must grow or procure the grain. Then they must grind the grain into flour.

I am told that it takes a women – on average – at least 4 hours a day to grind enough grain for her extended family to eat for a day. Four (or more) hours a day! Furthermore, I am told that grinding mills exist which could reduce that 4 or more hours to less than 1 hour per day – and that the Bishop wants to get those mills into Lui so that the women will have time to attend literacy classes. How can we not provide those grinding mills?!?!

I am told that it takes a women – on average – at least 4 hours a day to grind enough grain for her extended family to eat for a day. Four (or more) hours a day! Furthermore, I am told that grinding mills exist which could reduce that 4 or more hours to less than 1 hour per day – and that the Bishop wants to get those mills into Lui so that the women will have time to attend literacy classes. How can we not provide those grinding mills?!?!OK. I need to say this as one who is very fastidious about using napkins and cutlery. For me, the most difficult adjustment about eating in Lui’s villages was getting used to eating without either of those things. No fork. No knife. No spoon. No napkin. [Fortunately, in the Lui compound, we did have spoons. But not in the other villages.] I had heard that one would eat with one’s hands. Having grown up eating barbeque and fried chicken by hand, that didn’t catch my attention. Then I got into the remote villages of Lui, where you’re eating beans and rice with your hands.

This was a very different experience. I was surprised that this was such a difficult adjustment for me. Reflecting on it afterwards, I got some perspective on why I had had such a visceral reaction against eating with my hands. In the U.S., from our earliest infancy, we are taught that eating with utensils is a sign of being a “big girl” or “big boy.” To revert back to eating with our God-given “utensils” [i.e., our hands] was a very jarring experience for me. (By the way, after the first day of having that experience, I took a bandana with me on the subsequent trips, and was able to use it – to my great relief.)

This was a very different experience. I was surprised that this was such a difficult adjustment for me. Reflecting on it afterwards, I got some perspective on why I had had such a visceral reaction against eating with my hands. In the U.S., from our earliest infancy, we are taught that eating with utensils is a sign of being a “big girl” or “big boy.” To revert back to eating with our God-given “utensils” [i.e., our hands] was a very jarring experience for me. (By the way, after the first day of having that experience, I took a bandana with me on the subsequent trips, and was able to use it – to my great relief.)There was a second hand-washing ritual in the villages I visited. After everyone had eaten, one of the local folks would again make the rounds with her water pitcher so that everyone could wash their hands.

Father Bob’s thoughts on Daily Bread in Southern Sudan are more profound and moving than I can live up to. So I’ll just follow-up his comments with a few more details about food and eating rituals as I observed them in Lui.

And, of course, I’ll go on and on and on …. You've come to expect that of me, right?

I’ll start by saying “amen” to Bob’s comment about their generosity. It’s more than humbling. The words fail me – when I, a plenty-plump American, realize that these folks are giving us more food in a day than they eat in a week.

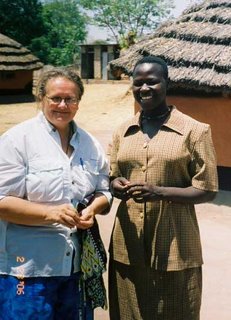

Here's Deborah with Anna, one of the women who prepared our food.

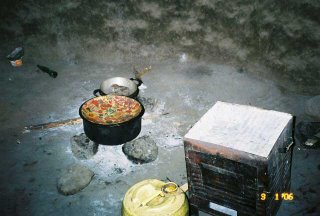

Here's Deborah with Anna, one of the women who prepared our food. After I had been there for a few days, the women allowed me to see inside the tukel where they prepared our food. Mind you, the temperature there is well over 100 degrees everybody day. And they cook this food inside one of the tukels – with fires burning, oven baking. I do not know how they endure that heat.

After I had been there for a few days, the women allowed me to see inside the tukel where they prepared our food. Mind you, the temperature there is well over 100 degrees everybody day. And they cook this food inside one of the tukels – with fires burning, oven baking. I do not know how they endure that heat.In the weeks before the trip, we received a “packing list” from the Diocese. It recommended that we all take 2,000 calories/day of “power bars” for the trip. Fortunately, Sandy was one of those who had said we could contact her for logistical assistance – since she had visited Lui two years before. So call her I did. And I vividly recall that conversation. I was simply thinking about my luggage and weight restrictions when I asked her, “Do we really need to take enough food to sustain us for the whole trip? Did you feel hungry while you were in Lui?” She replied in a careful way. Here’s what I understood of her reply. No, she had not felt hungry. To the contrary, when she looked around her and saw how starved people were, she just lost her appetite, so – even though she didn’t eat as much as she would have eaten in the U.S. – she never felt “hungry” in Lui.

As it turned out, I had exactly the same experience. Once I came home, people asked me about the food. “How was it?” “Were you hungry?” It just does not compute. To be brutally (and perhaps too frankly) honest, the food in Lui was mostly a “dud” for me. I didn’t enjoy any of it. (Except for the awesome greens we had on the last day there – about which, more later.) It was repetitious. How many meals in a row do you want to eat rice and beans?? And it was under-seasoned for my American palate. (But I understood that, for they can’t even get salt without importing it and paying a premium price.) But ya know what? None of that mattered!! Meals in Lui are not “events.” You merely need enough food to keep body and soul together, as the saying goes. Something weird happened in Lui. Food just quit mattering. I hope future travelers to Lui have the same experience.

I promised to talk about the “greens” we had on that last day in Lui. Having not seen a single vegetable the whole time in Lui, when we found greens on our dinner table that day, some of us were way beyond jubilant. I asked what kind of greens they were – collards? mustard? turnip? I could not imagine. Deborah advised we just eat and enjoy them and inquire later. And so we did. … Later she led me to the kitchen where I talked with our cooks and asked them about the source of those wonderful greens. Our cooks did not speak much English, so much of the exchange was through hand-gestures and scant English. But if I understood correctly, the “greens” were the leafy part of the bean plant. Head-slap to myself! Of course! In a place where every plant must be worked out of the soil with massive labor and resources, of course one would use that plant to the max! The wonder of it – as I realized – is that we harvest beans and peas and discard the leaves. How smart that they would harvest and use the foliage of the bean plants!

More from the Rev. Bob Towner, rector of Christ Church, Cape Girardeau

Our team of Missouri missioners was kept very busy twelve hours a day. For the other twelve hours, we were glad to return to our compound. This tall grass enclosure with several mud and grass guest houses, a common room, and service buildings, came to be “home.” Rick, the carpenter promoted to Master Builder, was my roommate. I was not left alone with the curious goats and hungry chickens and rats, the lizards and the toads. The extreme dryness which was a curse by day was a blessing by night. We did not have mosquitoes (malaria delivery systems), so we soon through off the stifling bed nets.

We would sit up in the dark, around a dinner table that had been carried into the open air. Kerosene lamps reflected off the faces of my companions. We had a whole new world and an entire new adopted family to discuss. A lull in the conversation led my eyes up to the huge, silent heavens, more loaded with stars than anywhere else I have ever been. I felt so small and yet, curiously, more a part of this beautiful little blue, green and brown planet than ever before.

Our compound was tucked between the two larger compounds, that of the Cathedral of the Diocese of Lui, and that of their hospital, staffed and funded by The Samaritan’s Purse (Read Luke 10:29 ff to refresh your memory of the meaning of this strange name.) Peter was the overseer of the guest compound, and he saw that his staff of two women and two men kept us safe and comfortable, clean and well fed.

How humbling it was to realize that they were sleeping with one eye open outside our huts. They were up before daylight, boiling water for our coffee, heating the huge drum of water for our sponge baths. They were quiet and gracious and ready with a smile, if they caught us looking at them in wonder. It amazed me to realize they stood ready to put themselves between us and any harm or danger that came our way. So deeply runs the privilege and duty of hospitality that they would rather die than see their guests die. “No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.” Jesus said that. Our Moru guests enacted it.

Only those who’ve camped in the rough have any idea of the great lengths our caretakers went to provide us with twelve hours of comfort and safety. Gathering wood and water are huge undertaking. Cooking over a fire is slow and hard on the back. Laundry was another daily chore, necessary because twelve hours of travel on red, dusty roads left us all caked in dirt. Once, sometimes twice daily, the whole hard dirt compound was swept with great grass brooms.

Hardest to understand was the generosity of our hosts when it came to food. We knew more than 90% of the children were malnourished. We knew that civil war and drought created the need for families to daily decide who needed most to eat and who could afford to go hungry. Yet, morning and night (and noon if we weren’t traveling), our caretakers arrived with white rice (imported), and large red beans. Sometimes there was homemade wheat bread, a rare treat in the Sudan. It is delicious served with stone ground sesame seed butter and back yard honey. Sometimes there was a Sudanese staple, stone ground sorghum seed, rolled into a big, floppy tortilla. We had a great laugh watching a young man chase down an old, wiry rooster one afternoon. His days of ruling the roost were over. He tasted so rich and nourishing, even if he was tough and stringy. Tomato sauce, scrambled eggs, small potatoes, and mixed garden greens were rare treats.

Our hosts spared no expense. Since returning three weeks ago, we have certain news that the last of the stored food in many of the villages we visited is exhausted. Even if rain comes, it will be many months before any crop can be harvested. Famine is a real and present danger. Since 1980 most of the rest of the world has been able to reduce extreme poverty and famine from 40% to 20%. The tragic exception is sub-Saharan Africa, where these figures have taken a turn for the worst. Extreme poverty has grown in this generation from 42% to 47%. This means almost half the people do not know where there next meal is coming from or if there will be one. When they pray, “give us this day our daily bread,” they know only God at work in the hearts of God’s people, will provide it.

Thursday, March 30, 2006

It was hot in Lui. Really, really hot. Every day it was more than 100 degrees, and usually it hit 110 degrees. (On our last day in Lui, my little thermometer said it hit 120.)

One would hope that things would cool down in the evening, before you have to go to bed. But it was typically 80-90 degrees at bedtime.

However, after a few days, Deborah clued us in on a trick she loearned from the Moru. An hour or so before you go to bed, pour some water on the bare-dirt floor of your tukel, and spread it around with the “broom.” Deborah swears that this treatment will cool the tukel by 5 to 10 degrees F.

This was a big surprise to me. When I was packing for the trip, I assumed I should pack all the clothes I would need for this 12-day trip. But you really don't have to. The women who take care of us in the guest compound are quite willing to do laundry. So if you pack 3-4 days of laundry, you can get by, by letting these women do the laundry occasionally.

But be aware of this one caveat: Undergarments are personal, and it's best not to ask the women to do those. You may pack with the plan that they’ll wash your shirts and skirts/slacks; but pack enough underwear to get you through the whole trip, or else plan to do your undies yourself.

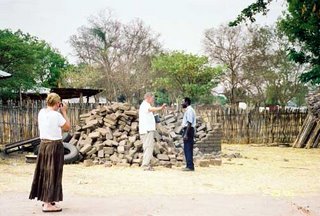

Our Man Rick was on the job!

Our man Rick was a walkin' talkin' plannin' conceivin' machine! He was always On The Job. Throughout our trip, he was forever talking with the Lui folks about what kind of structures would suit their needs and be long-lived. This is just one of the hundreds of photos we could have captured where Rick was working with Peter or other folks in Lui. I caught him here with Peter, and Sandy (at left) is taking their photo.

The kitchen they now have (adjacent to the Guest Compound) is not large enough for their needs, and it has no storage. This is the new kitchen structure they are building. Pictured here are Sandy, Lisa, & Deborah.

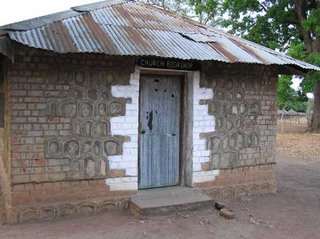

This is Morris’s bookshop. In it, he has many copies of the Moru Bible and the Moru prayer book, as well as a library he is building.

This is Morris’s bookshop. In it, he has many copies of the Moru Bible and the Moru prayer book, as well as a library he is building.Here, Deborah is showing us the structure that the Mother’s Union is converting into a new sewing center.

This is the present sewing center. Deborah is showing Sandy how the women operate the treadle machines they have received.

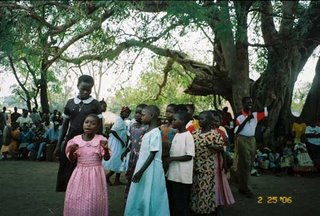

Once I left the folks with whom I had shared the audio recordings, I resumed my course: heading for the music festival under Loru. If I understand correctly, they have this event on the last Sunday of each month. Some folks called it a music “competition.” But after seeing it, I term it a “festival,” for there does not (to my eyes) seem to be much of competition about it. Instead, it seems to be everyone doing their best, and all the watchers/hearers appreciating them.

As I approached this gathering – even from a distance – I could tell it was a “big deal.” Folks were gathering from near and far.

As I approached this gathering – even from a distance – I could tell it was a “big deal.” Folks were gathering from near and far.I came in alone, and began circling the crowd in search of a good vantage point. Eventually, I found a space that I thought was good, with a clear line of vision. But about the time I settled into that space, a man who (I later observed) was functioning as "emcee" approached me. He held his stick out to me, and made it clear that I was to move. I thought he was doing so because I had broken some rule. But no! He was leading me to another spot – to a seat in the inner circle. And then I saw that Sandy was also seated there, so sit I did.

The singing was wonderful! Group after group came forth to offer their performance.

And this is one reason I said it is not a “competition,” but a “festival.” Once I had settled in, and the first group I heard finished their singing, there was no applause – as we would expect in the U.S. Instead, the guy who functioned as emcee did this interesting thing. He “warmed up” his hands, and raised them up high, then led the whole group in one loud, simultaneous “clap.” Then he did the same “warming up his hands” down low, and led the whole group in one “clap.” Later, somebody explained the two “claps” to me: They make one clap to God (up high) and one for us (down low). I like that. But I also like the other dimension that I perceived: By making only two “claps” for each group, you don’t have the situation where one group might get thunderous applause and another get only minimal applause. Everybody gets exactly the same applause – one high, and one low – for their offering.

We saw and heard group after group singing wonderful music and doing marvelous dance.

One of the groups did a performance that I can only describe as a “morality play." They paraded in as all the other groups had done. But then one girl, who was leading the line, was approached by someone who whispered in her ear. Then somebody else whispered in other people’s ears. Then those folks started gyrating wildly. Eventually they fell down on the ground in spasms. Then one character appeared, with a paper bag over his head on which were painted the markings clearly meant to identify him as The Devil. And this guy did a great “Devil” impersonation – flicking tongue and all! In the drama that unfolded, you could see that he had seduced these people. But then some of the other people around piled brush in a square pattern and threw him down into that brush pile and set it on fire!

In the center of this photograph, you can see the “Devil” character with the paper bag “mask” on his head. He is being subdued by the people, and you can see a young man to his left setting the fire.

In the center of this photograph, you can see the “Devil” character with the paper bag “mask” on his head. He is being subdued by the people, and you can see a young man to his left setting the fire.After the “Devil” was “killed,” the people who had been seduced by him fell down on the ground, and other people splashed water on them – suggesting the waters of baptism or purification. And then they arose whole and healthy again.

WOW! What theater!!

And over all this experience, I was mindful that these folks were assembled under the Loru tree – symbol of their oppression, liberation, and newfound hope.

In the midst of all that energy, my own little drama pales by comparison. You Episcopalians reading this are well aware that we just do not pray extemporaneously! But the Episcopalians of Lui do! And roughly midway through this 2- or 3-hour music festival, one of the Lui folks approached me and said they had decided I should offer the closing prayer at the end of the event. YIKES!!! Me, asked to pray, and my Book of Common Prayer nowhere at hand!

My anxiety was all the greater because I had – by this time – been living with these folks for three days and had heard their most earnest, intense prayers – delivered extemporaneously. I would have to “wing it.”

I have no idea how the prayer “sounded,” but I can assure you it was the most intense prayer I ever prayed in public.

We had heard that the Lui Diocese had a farm and wanted recommendations about how to make it more productive. Sunday afternoon, some of our group went on a trip to that farm. I was not there; I only heard the stories.

We had heard that the Lui Diocese had a farm and wanted recommendations about how to make it more productive. Sunday afternoon, some of our group went on a trip to that farm. I was not there; I only heard the stories.The diocese has suffered greatly under the drought. Here is one of the plants. I don't know a whole lot about farming, but I think I know enough to realize that this is a pitiful yield for farmers who have been tending their crops all through the meager growing season!

I understand that the river is very close to the farm. But there is no technology to pump the water up the farm, and certainly no system for irrigation. So the crops are at the whim of the rains and drought.

When our friends returned to the compound, this led to much more discussion. How – how?? – can we begin to help them address all these problems? To save the crops, they need water. To get water, they need a pump of some sort. To operate a pump, they need energy of some sort. But there is no electricity, and no operating “alternate energy,” – and darned if I can think of how to provide it as quickly as they need it, they who even now are enduring a massive drought that reduced their harvest last fall to 20% of the normal harvest.

When the diocesan staff thrust a digital audio recorder in my hands, saying, “Here! Figure it out!” I was more than a little non-plussed. I am not a techno-whiz. But with Rick’s help, I figured out the basics of how to operate the darn thing. And I recorded much of the music in the Sunday services.

The pay-off came after church on Sunday. I went strolling around the compound, heading toward the music festival. But I encountered Deborah under the big mango tree, preparing to teach a Bible study class.

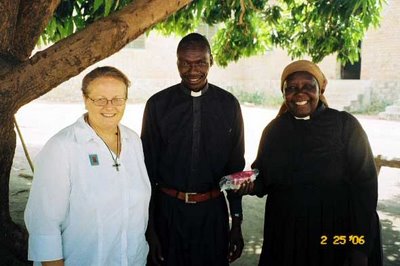

Here is Deborah with Sylvester and Mama Margaret. Deborah had just given them the anointing-oil that our Bishop had blessed.

But more mundane treats were to come!

I don’t know what made me do this, but I showed Deborah and her friends the audio recorder and asked if they might like to hear the music I had recorded in the Cathedral this morning. Boy, did they!

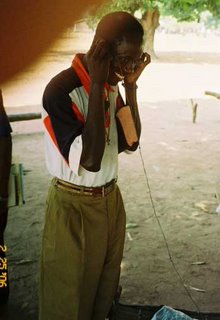

I gave Mama Margaret the headphones, and she burst out in a wonderful smile and immediately started moving with the music.

Then Sylvester started moving and smiling to beat the band too!

The longer we stayed under the tree, the more people gathered. It seemed they all wanted to hear this music which they had created, but I suppose they had never heard it before.

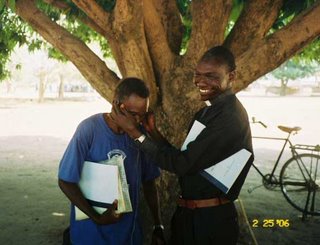

Once I had introduced them to the technology, they were eager to share it with each other. Here, William is at the left. His smile alone is testimony enough for the pleasure he gained from those sounds.

Sylvester shares the joyous sounds with Morris.

Pretty soon, I noticed that children were gathering around, curious about what we were doing. I had to gain this girl's confidence. She did not seem to know what we were putting these people's heads. So I knelt down in front of her, put the headphones in my own ears, then gestured, asking if I could put them in hers. And she did. And the smile she gave when she heard the music was ... well ... worth its weight in gold.

It was so much fun to share this music with them! One of the fun things the photos cannot capture: Everyone who put-on the headphones immediately started moving or dancing to the sounds of the music. And then I would notice it, then they would notice it, then we would both break out in hilarity.

This was a very, very good day. I hope the photos will speak for themselves.

And our diocese has hopes of putting audio onto this webpage. I hope they'll be able to do it soon.

Wednesday, March 29, 2006

Previous missioners to Lui had told us to expect this. The people of Lui do not have money. I’m not even sure there is a functioning currency in Lui. So when they go to church and the offering is collected, it is nothing like it is here in the U.S. where we put our cash and checks into the offering plate. It’s more like I imagine it was in the early days of Christianity. People bring whatever gifts they have. It may be a scant handful of seeds or grain. It may be a piece of fabric. It may be a pretty leaf or rock that a child has found.

Previous missioners to Lui had told us to expect this. The people of Lui do not have money. I’m not even sure there is a functioning currency in Lui. So when they go to church and the offering is collected, it is nothing like it is here in the U.S. where we put our cash and checks into the offering plate. It’s more like I imagine it was in the early days of Christianity. People bring whatever gifts they have. It may be a scant handful of seeds or grain. It may be a piece of fabric. It may be a pretty leaf or rock that a child has found.And they do not just pass the offering plate among the pews. One or two people stand up near the altar, and the people come forward with their offerings.

This was the first place where our lack of “spendable” currency struck me. We had (by comparison) so much material wealth! But we had no currency that they could use. Fortunately, Archdeacon Robert would slide some Ugandan dollars into our hands, and we would contribute that. But after my first day out in the villages, I learned to “pack an offering.” One of the things I had heard was that they yearned for pens and pencils, and I had brought dozens of those with me on the trip. So each morning before heading out, I would grab several of those, and – when the offering came – share them with the other missioners so we could put them into the offering basket. I think this experience will forever change my experience of how we collect the “offering” in our parishes in the U.S.

Turn up the volume and listen to this music while you read this blogpost. This is some music I recorded during the Cathedral service on this Sunday.

The second service (the “English” service) had a good attendance. But the third service was the big one of the day.

The second service (the “English” service) had a good attendance. But the third service was the big one of the day.The cathedral was full to overflowing. This was the moment where it also became clear they had prepared special greetings for these “honored guests.”

One highlight of the service was when a group of their young people came singing and dancing down the center aisle. The intensity of their singing was overwhelming to me. I think this was the moment when I became overwhelmed by the intensity of their faith.

For our trip, the Diocese purchased an digital audio recorder, and I was made “Sound Technician.” Previous missioners to Lui had returned with photographs and stories, but they all said that the “missing element” was the music. There’s an intensity and “primal-ness” to it that you just cannot describe. I was glad to be able to record much of this music, which we’ve now handed over to the Diocese in hopes that they can distribute it more widely.

I am told that when Bishop Bullen visited St. Louis last fall to explore entering into a companion relationship with the Diocese of Missouri, he visited the Forsyth School in St. Louis . I understand he got excited about the concept of establishing a “companion relationship” between the Forsyth School and the schools of Lui, similar to the companion relationship he was forging between the Diocese of Lui and the Diocese of Missouri.

God bless ‘em! The kids of the Forsyth School – having met Bishop Bullen and having heard some of his stories – took it to heart. They made a book for the children of Lui. The Forsyth students wrote about the things they treasure here, and drew illustrations to accompany their words. Also, they collected money and bought an American football, a soccer ball, and a kickball. They asked us to carry those items to Lui for them.

The plan was great. We would give the books and balls to the children of Lui. They would write their own stories and draw their own pictures, and we would bring them back to the U.S., and continue to send that book back and forth, so the kids could swap stories.

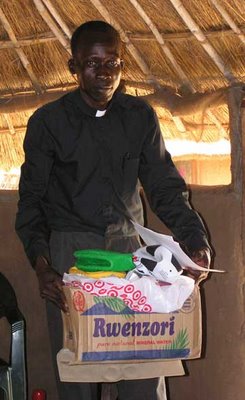

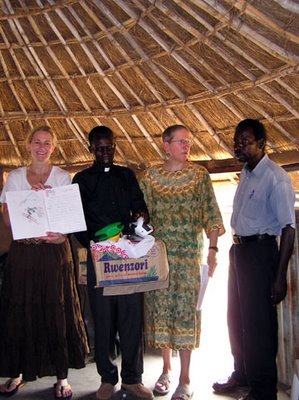

We carried the book and the balls to Lui. On Sunday afternoon, we presented these gifts to the Lui clery.

Here are Deborah, Sandy (holding the Forsyth students’ book), Vasco (holding the box full of balls), and Lisa.

Here are Deborah, Sandy (holding the Forsyth students’ book), Vasco (holding the box full of balls), and Lisa.

The plan was great! But there was one problem. The drought in Lui has been so devastating that Lui had to close its schools back in the spring. The Lui children cannot remain in school because there is no water. Here in the U.S., we are accustomed to having the occasional “snow day.” But in Lui they have had to close the schools because the children would die without water. And whereas I remember welcoming “snow days” as a day out of school, the kids in Lui are desperate to be back in school. There’s something really wrong with that!

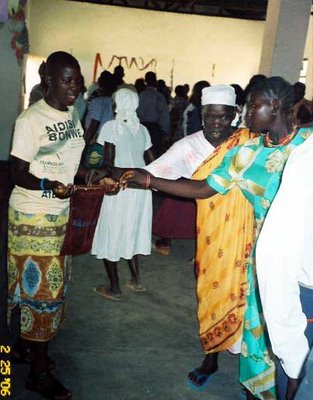

One difference between their service and ours especially struck me: they do not “exchange the peace” during the liturgy. But they have a wonderful variant, which several of us thought we would love to see introduced in the U.S.

When they recess out of the church after the service, the first person out [I think it was the Bishop] seeks the nearest shade and stops. Then the second person shakes his hand in greeting and stops just beyond him. Then the third person greets the first and second, and stops just beyond them. And so on and on. So the result is that every person present greets and shakes the hand of every other person. It’s a very warm, celebratory part of the experience.

Oh! and by the time most of the group has moved outside, the drummers and singers are also outside, so the music goes on and on.

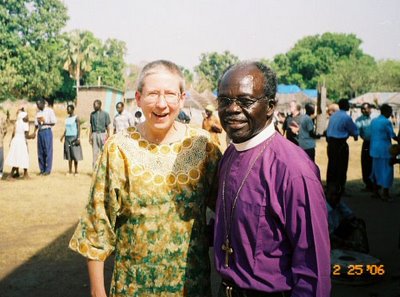

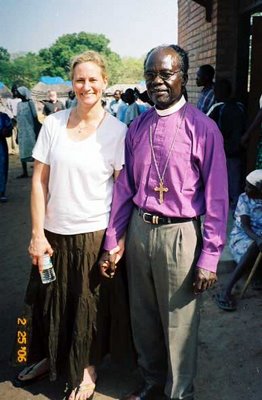

After the service, “the girls” had photo-ops with Bishop Bullen.

The first is Lisa with the Bishop.

Then Sandy & the Bishop.

It’s embarrassing to me to acknowledge this. But after a mere 3 weeks, I am not sure what the schedule of services was in Lui that Sunday. I know they had multiple services. I believe they had three services. I can’t recall what the first service was, but I do recall that Rick was the only one of our group who got himself up and at ‘em to attend all the services.

The second service (which all of us attended) was their English-language service. But it was not just native-English-speakers who attend. Lots of the Moru attend too. I wonder if this is because so many of the folks in Lui are working to improve their English-speaking skills.

Father Bob got the distinction of getting to preach at that service. I think he had a little more than 12 hours notice of this assignment! This was taken as Bishop Bullen was introducing him.

Father Bob got the distinction of getting to preach at that service. I think he had a little more than 12 hours notice of this assignment! This was taken as Bishop Bullen was introducing him.Notice to future Lui missioners: It’s not just priests who are asked to preach in Lui. In a fundamental sense, they really do believe in “the ministry of all the baptized.” You might be asked to preach – either in the Cathedral or in the Samaritan’s Purse chapel – almost at the drop of a hat. Go prepared with some texts that speak to you. And another difference: They don’t preach from the lectionary as we do. I can’t remember who told me this story, but someone was asked to preach and inquired what were the lectionary readings for the day, and was told, “Whatever’s in your heart.” This is very different for us lectionary-bound Episcopalians!

Similarly, be prepared to be asked to teach without much notice. Father Bob was told Friday evening that he was expected to teach a day-long workshop for the youth leaders the next day. On a previous trip, Sandy was informed that she would be teaching a day-long workshop on AIDS education. Person after person has recounted similar experiences. The folks in Lui are truly hungry for education, and they’ll tap anybody for a training session or a sermon.

We also picked up this perspective about their preaching, speaking, and training: It all must be Bible-based! Even if you’re talking with them about agriculture, try to have a Bible verse handy. On our team, Sandy had brought a nifty Bible reference book, and others might want to be sure take a similar resource.

The Moru Prayer Book is based – I hope I got this information correctly – on the 1662 English Book of Common Prayer. So the structure of the liturgy will not be completely “in synch” with what we U.S. Episcopalians have come to know.

This struck my memory, though. The Diocese of Lui does not seem to have the high “Eucharistic” view that U.S. Episcopalians do. In Lui, only a few services include the Eucharist. But they do celebrate the Eucharist on the last Sunday of the month, and we had the good fortune to be there on that Sunday. Apparently, many people in the Lui diocese attempt to make it to the Cathedral for this last Sunday of the month. So that made this day extra special.

I’m not sure whether the appearance of the churches is a function of the “low-church” theology or of the poverty of the area. But I was also struck by the simplicity of the decoration. This is a shot of the cathedral’s chancel.

With all the fuzziness of my brain, this one memory does remain vividly clear: Father Joseph Phillip (Dean of the Cathedral) went through the prayers of consecration. Then other clergy began administering the bread and “wine.” But it was not “wine.” The Christians in Lui do not drink alcohol at all – even at communion. Instead, they use and consecrate a deep-red tea made from hibiscus blossoms. (It’s quite tasty, in fact!) The reason they don’t use wine is that alcohol abuse is a real problem in this region, and they have taken the stance that Episcopalians just do not use wine.

But what struck me was that Father Joseph Phillip had to consecrate chalice after chalice after chalice of that drink. Here in the U.S., we take a dainty sip from the chalice. But as I sat there in the front of the chancel, I realized eventually that these people were really drinking -- not just sipping daintily from the chalice. It took me a while to figure out what was happening, but finally I did. In Lui, water is in short supply. And “healthy” water is in even more short supply. When we administer the chalice, we say, “The Blood of Christ, the Cup of Salvation.” But in Lui, the chalice from which they drink is the cup of salvation on so many more levels. It’s probably the only decent drink they will get all day. And it is the Eucharistic drink. In that setting, I had a much stronger sense than ever before that the body and blood of Christ truly is sustaining us.

Last weekend I received the wonderful cache of photographs that Archdeacon Robert took during our trip. So I am returning to some of the previous posts and adding more photos and some commentary/thoughts that those photographs recalled for me.

To be sure you're seeing the entire blog, click on the March 2006 entry under the "Archives" heading over on the right-side of the screen. That way, you'll see everything we've put here, instead of just what's on the "front page" of the blog.

And, remember, if you want to read the entries chronologically, you'll have to read "from the bottom up," because that's how Blogger organizes them.

Friday, March 24, 2006

Saturday afternoon, our whole group had some leisure time -- probably for the first time since we left St. Louis. Some of us enjoyed visiting and getting acquainted. [At left are Lisa, Sandy, and Deborah.] Then we all took the opportunity to explore Lui.

First we came upon a large group of children playing soccer.

We stood awhile, just enjoying them.

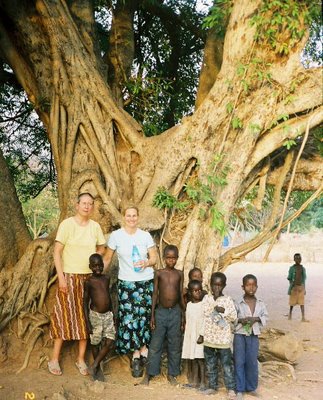

We stood awhile, just enjoying them.Then Sandy and I found ourselves at the famed (in Lui, at least) Loru tree. (Or is it Laru?)

Previous travelers to Lui had told us about this famous tree. And during our stay in Lui, we heard many references to it. In the 19th century, when the slave trade was at its height, people from other parts of Africa had come to southern Sudan and captured people to sell them into slavery. The slave auctions were held under this tree named Loru. When Fraser came to Lui in the 1920s, he was appalled by these stories and – desiring to create schools – he established one of the first schools in Lui in benches positioned under this tree. So he transformed this tree, which had once been a symbol of slavery, into a symbol of freedom. It appears that the tree still has great mythopoeic power to the people of Lui.

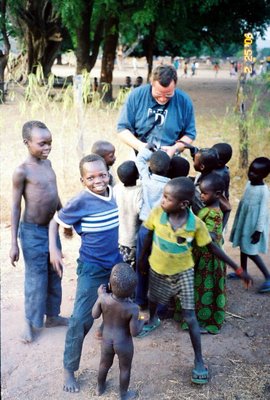

Previous travelers to Lui had told us about this famous tree. And during our stay in Lui, we heard many references to it. In the 19th century, when the slave trade was at its height, people from other parts of Africa had come to southern Sudan and captured people to sell them into slavery. The slave auctions were held under this tree named Loru. When Fraser came to Lui in the 1920s, he was appalled by these stories and – desiring to create schools – he established one of the first schools in Lui in benches positioned under this tree. So he transformed this tree, which had once been a symbol of slavery, into a symbol of freedom. It appears that the tree still has great mythopoeic power to the people of Lui. As we walked about the village, taking in the sights, we were struck by how many children were out and about enjoying this pleasant afternoon. But we did not anticipate this: Archdeacon Robert had brought his digital camera on the trip, and was merrily clicking away. He soon began letting the children see the display of the photos he had taken. Before long, he had a mob of kids around him, all wanting to see these photos!

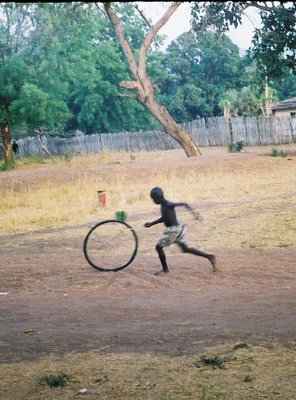

As we walked about the village, taking in the sights, we were struck by how many children were out and about enjoying this pleasant afternoon. But we did not anticipate this: Archdeacon Robert had brought his digital camera on the trip, and was merrily clicking away. He soon began letting the children see the display of the photos he had taken. Before long, he had a mob of kids around him, all wanting to see these photos!One thing that shocked me was seeing a little boy playing this ancient game.

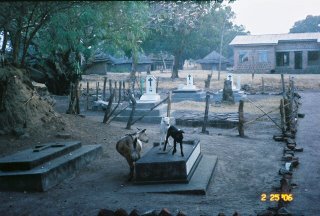

Throughout Lui, there are two types of “livestock”: chickens and goats. Both are (I suppose) maintained for their food products of one sort or another. When we were there, the goats had just recently had lambs, which seemed quite dear to us. But this image caught my attention – the goats and lambs frolicking upon the graves in the Lui cemetery. Something weird about that! [EDIT: OK, more than one of you has told me that the "something weird" about that whole thing is that goats do not have lambs; they have "kids." I'm glad to know you folks are reading carefully!]

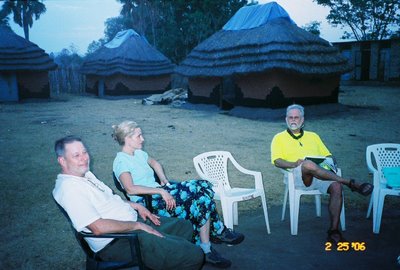

Throughout Lui, there are two types of “livestock”: chickens and goats. Both are (I suppose) maintained for their food products of one sort or another. When we were there, the goats had just recently had lambs, which seemed quite dear to us. But this image caught my attention – the goats and lambs frolicking upon the graves in the Lui cemetery. Something weird about that! [EDIT: OK, more than one of you has told me that the "something weird" about that whole thing is that goats do not have lambs; they have "kids." I'm glad to know you folks are reading carefully!]  At the end of the day, we returned to the guest compound, where we were treated to another good meal (thanks to our Lui hosts!). Here, Rick, Sandy, and Father Bob are relaxing as evening comes on.

At the end of the day, we returned to the guest compound, where we were treated to another good meal (thanks to our Lui hosts!). Here, Rick, Sandy, and Father Bob are relaxing as evening comes on.One of the things I enjoyed about our trip was the companionship. In our “normal” lives in the U.S., we would have retreated to our hotel rooms, watching some sort of mindless television. But Lui has no electricity – much less television. So the way we entertained ourselves after dark set in at 6:30-7:00 p.m. was by visiting, talking, sharing stories. Every night, we had at least three hours of conversation before turning into bed around 10:00. It was a healthy way to wind up the day.